Taking Aim at a Deadly Enemy: A personalized approach to combat lung cancer

Prof. Tony Mok

Department of Clinical Oncology

It is through the emerging field of personalized medicine that CUHK professor and oncologist Tony Mok has been improving the treatment and lives of lung-cancer patients. As the lead investigator on two landmark studies, he has helped to establish new approaches to the treatment of lung cancer that can extend the lives of people afflicted by the disease.

Professor Mok has been tracking patients with what is known as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation, an oncogene that can cause normal cells to become tumorous and that results in thousands of lung-cancer cases every year. He has established that it can be more effective to treat advanced lung cancer caused by the EGFR mutation with a pill that a patient can take once a day, without the need for chemotherapy, which is more toxic.

Lung cancer ranks narrowly behind colon cancer as the most common form of cancer in Hong Kong. The city reports 4,000 new cases of lung cancer each year, and there are around 1.3 million new patients per year globally. The EGFR mutation is more common in Asia, accounting for around 30% of lung-cancer patients, and as much as 50% of nonsmokers with the subtype called adenocarcinoma, which stems from glandular tissue and the inner lining of the lung.

In the EGFR mutation, a genetic defect on the receptor causes a malfunction, providing a continuous growth signal to the cancer cell, which then grows uncontrollably. The drug gefitninib, marketed under the name Iressa by AstraZeneca, inhibits an enzyme, tyrosine kinase, which acts as the “on” and “off” switch for the signal. It binds with the tyrosine kinase, and inhibits the enzyme, meaning the signal is no longer sent.

Professor Mok oversaw the Iressa Pan-Asia Study, or IPASS, the study that first established the foundation for using personalized, gene-based medicine to treat lung cancer. After the New England Journal of Medicine published those findings in 2009, all patients with adenocarcinoma are now mandated to be tested for the EGFR mutation.

Following another ground-breaking discovery in Japan, that the re-arrangement of an enzyme known as anaplastic lymphoma kinase or ALK can also cause lung cancer, Professor Mok launched another major study known as PROFILE 1014. Again, the ALK abnormality can be traced through genetic testing.

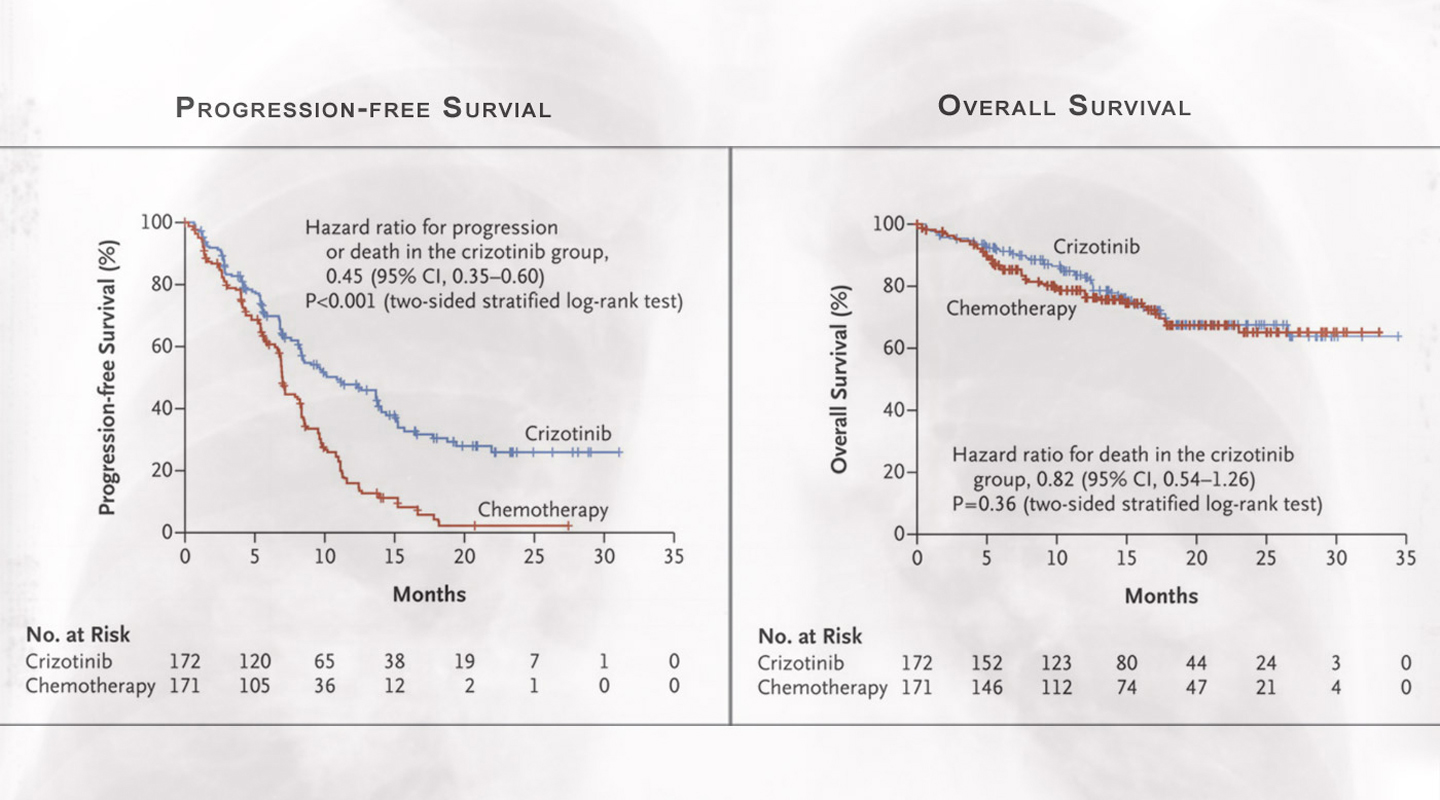

PROFILE 1014 looked into the use of another drug, crizotinib, that inhibits the ALK. The study, conducted with Prof. Benjamin Solomon at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, confirmed the superiority of crizotinib over chemotherapy, findings that came out in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2014 (see the excerpted graphs in photo above).

Unlike EGFR, ALK is not a mutation but instead involves the translocation of chromosome 2. What used to be an “indolent” gene causing little or no harm suddenly becomes a fusion protein that makes the ALK active. Treatment with crizotinib showed substantially better results than chemotherapy in terms of extending the patients’ lives.

His results show that all patients with advanced-stage lung cancer should be tested for the EGFR mutation and ALK rearrangement. They can then receive the appropriate drug. Thanks to this work, such personalized medicine is now a universal standard, allowing for individualized plans of treatment based on each person’s genetic makeup.

Lung cancer remains the most fatal illness, with over 70% of patients diagnosed only when they already have highly advanced cancer. Previously, the median survival time for patients with Stage 4 lung cancer was less than a year. Thanks to the new methods of treatment, that timeframe has extended to between three and four years, when the right gene is detected and the cancer targeted with the right drug.

“The whole objective is to convert a fatal lung cancer into a chronic illness,” Professor Mok says. “We are not curing the patients with advanced-stage lung cancer. But people can take one pill a day, and they live like a normal person for a substantial portion of time.”

Professor Mok credits much of his success to collaboration. He founded the Asian Lung Cancer Research Group in 2000, and is the current president of the International Association on Study of Lung Cancer, which has some 4,000 members.

“I’m only part of the movement – it is a global collaboration,” Professor Mok says. “I was fortunate enough to have a lot of good partners, particularly in China.”

In particular, he has worked over the past 16 years with Prof. Wu Yilong in Guangzhou, whom he considers the leading lung-cancer expert in China. Access to an extensive patient database from China has led to rapid improvement of the understanding of the disease in this part of the world.

“Asia was not really on the map for lung cancer research before 2000,” Professor Mok says. “That is a golden opportunity for us to contribute and make a difference.”

By Alex Frew McMillan

This article was originally published on CUHK Homepage in Dec 2015.