Remembrances of Things Past and Sunk

On the rescue of underwater cultural heritage and the evolving international laws

With its unfathomable depth and buried mysteries, the sea has long charmed mankind. Works like Treasure Island and Pirates of the Caribbean speak to our adventurous fancy and fill us with romantic notions about the sea, piracy and treasure hunting. While what historians call the Golden Age of Piracy (the period from the 17th to the 18th centuries) is long gone, treasure hunting is still very much alive, the treasures today being none other than corpses of ships lost in the angry waves. What modern treasure hunters gain are often losses in archaeological and human terms. In many cases, the law comes to the rescue and is used as Poseidon’s trident to settle and subdue; but can it?

In the fifth lecture of this year’s Greater China Legal History Seminar Series held on 22nd February titled ‘Chinese Shipwrecks, Treasure Hunters and the History of Underwater Cultural Heritage Regimes’, Prof. Steven Gallagher, Associate Dean (Academic Affairs) at the Faculty of Law, walked the audience through the fate of the vessels lying in the placid depths, what international laws and conventions come into the picture and how Hong Kong and China fare in preserving their underwater cultural heritage.

Law of Salvage as Shipwreck Legacy

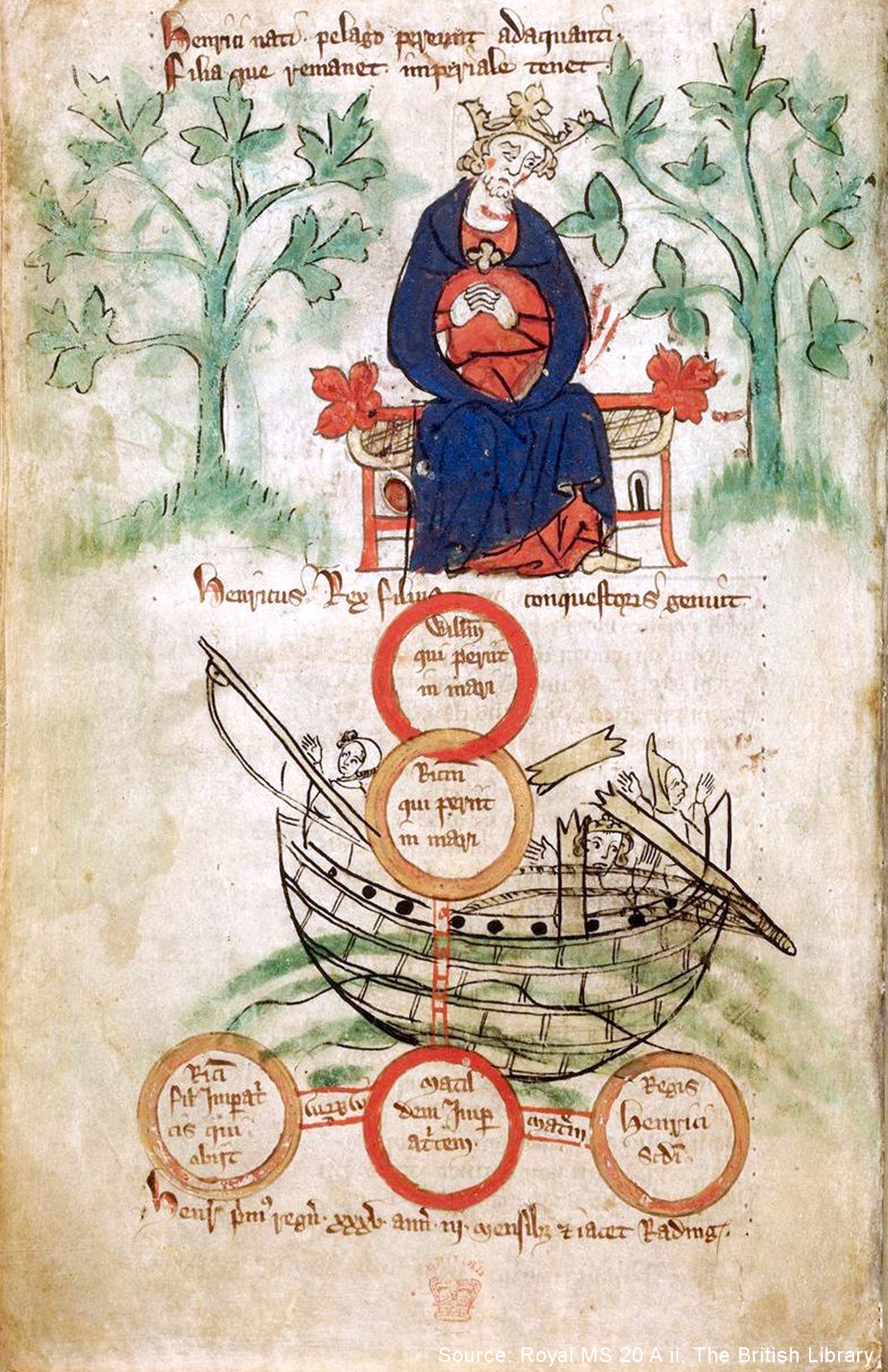

Far from being unlawful, the modern treasure hunters’ claim to the vessel’s valuables is legally established by the law of salvage. As the root of salvage (save) indicates, the law of salvage encourages the saving of lives, ships and cargo in peril, through entitling voluntary salvors to an economic reward for a wholly or partially successful recovery. The birth of the law can be traced back to a shipwreck in the 12th century—that of the White Ship. Today, the law of salvage applies to most jurisdictions around the globe.

Who Owns the Bounty at Sea?

Salvage law offers economic rewards but not ownership to the salvor. As to who owns the treasures, the location of the wreck is important, as under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (1982), a country has complete sovereignty over waters 24 nautical miles (around 44 kilometres) from its coastline and owns whatever is found within. Warships and government ships enlisted for non-commercial purposes, however, enjoy sovereign immunity. In the latter case, their originating countries’ right of ownership supersedes that of the state in whose waters the wreck lies.

That still leaves a big pie for the finders keepers: for wrecks recovered in international waters, provided that the owner cannot be traced, or that they are not from military or government ships or if the relevant sovereign state disowns the wreck, the treasure hunters are allowed to claim ownership of them.

Shipwrecks as Cultural Heritage

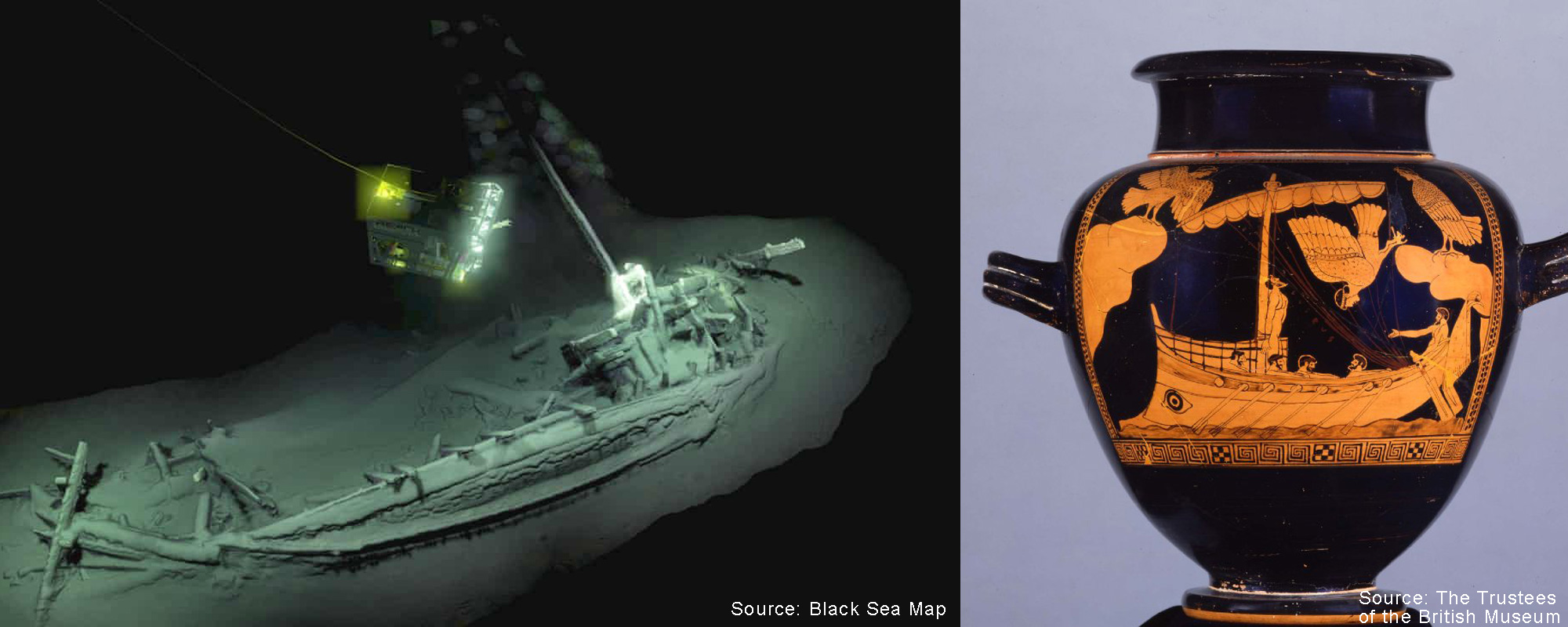

Dividing up the treasures is not the end of the story. The sunken riches are treasures not just in economic or monetary terms. ‘The shipwrecks are treasures in many ways. They are underwater cultural heritage (UCH) which tells the customs of people, interactions between nations, and the national and individual endeavours undertaken in trading on the dangerous seas,’ explained Professor Gallagher.

From an archaeological perspective, the deep-sea vessels make good objects of study as most often they have been untouched by man for a long time and remain well preserved. More subtly, wreck sites are often graves of human remains. To venture in and loot them as treasures is often deemed an act of desecration.

What does the Law Do to UCH?

To prevent pure commercial exploitation of the salvage, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared the Convention on the Protection of the UCH (CPUCH) in 2001. UCH is given a more rigorous definition than in UNCLOS as sites, structures, vehicles, artefacts and all other traces of human existence having a ‘cultural, historical or archaeological character’ that have been wholly or partially under water for at least 100 years. Pipelines, cables and installations placed on the seabed and still in use are not counted as UCH.

CPUCH reaffirms the importance of UCH as ‘integral part of the cultural heritage of humanity’ and ‘a particularly important element in the history of peoples, nations, and their relations with each other concerning their common heritage’. A big leap from UNCLOS which steers clear of the law of salvage, CPUCH stipulates clearly that the salvage law does not apply to UCH. Instead, in situ preservation is preferred as the first option, and there should be no commercial exploitation. On the touchy subject of human remains, the convention also mandates special treatment.

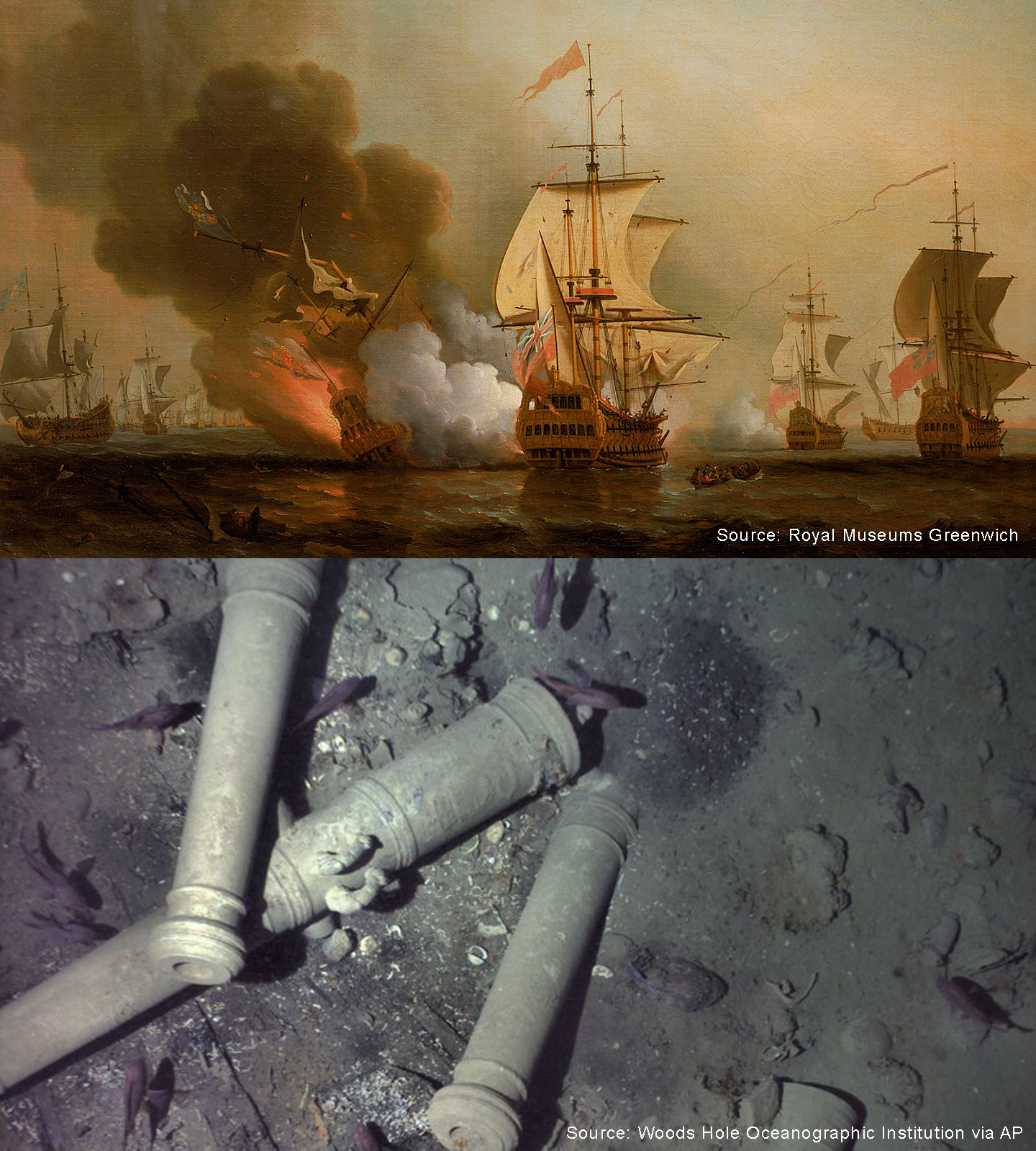

It is obvious that CPUCH, which stresses the common good, and the salvage law, which endorses the capitalist spirit, are uneasy bedfellows. Despite painting a desirable picture, CPUCH is much limited in powers, as the major maritime powers, except Spain and Portugal, all refrain from signing the convention. Hugely lucrative commercial ventures, including Odyssey’s Black Swan project and the Belitung Tang wreck project, still took place. Moreover, many WWII wrecks in Southeast Asian waters yet to reach the 100-year threshold are now being plundered for scrap metal and for valuable pre-nuclear age radiation-free steel plating. As Professor Gallagher remarked, not without a hint of regret, ‘Cultural heritage laws are mostly aspirations; they are not laws.’ Poseidon’s trident, it seems, is no match for human avarice.

How are Things in China?

Back to the ‘Chinese shipwrecks’ in the lecture title, China’s involvement in rescuing its national and cultural patrimony is fuelled by a major disappointment in 1985 when it did not have enough capital to buy the 150,000 Chinese porcelains—the Nanking cargo—auctioned in Christie’s. Since then, the country has spared neither money nor efforts in securing and publicizing its submarine treasures. In 2007, Nanhai No. 1, a vessel sunk in early Southern Sung dynasty and the oldest and largest of its kind ever found in China, was raised from the South China seabed. The Maritime Silk Route Museum was built to house the haul and let visitors watch the excavation process.

What about Hong Kong?

UCH is particularly important to Hong Kong, a city that thrives upon maritime trade. The recovery and study of UCH can shine light on its long maritime and trade history even before the colonial period. In Hong Kong, the protection of UCH is mainly delivered by two ordinances. The Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance (EIA) ensures that Heritage Impact Assessments are carried out at the early planning stage of all capital projects, and with underwater projects, Maritime Archaeology Investigation must be conducted.

The second ordinance in force, Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (AMO), protects the UCH by recognizing artefacts, sites or structures made by humans before 1800 as antiquities or relics, or declaring sites or structures that possess historical, archaeological or palaeontological significance as monuments. As to their effectiveness, Professor Gallagher observed, ‘The ordinances and assessments are great systems. The matter is whether they are followed.’

What should Hong Kong further do to protect UCH? Professor Gallagher, an equity and cultural heritage law professor, cited the opinion expressed in a proposal co-authored by Dr. Bill Jeffrey and the Hong Kong Maritime Museum: to create an inventory of all of the city’s UCH and to identify significant sites and nominate them as monuments under AMO, among others. He added, ‘The cost of all these is just three million Hong Kong dollars, with dollar matching by the Museum. It’s not as costly as some of the city’s public works, and far less than the US$32 millon Singapore spent on the Tang wreck. It’s money well spent.’

Originating from the popular Chinese Customary Law Seminar Series held from 2014 to 2016, the Greater China Legal History Seminar Series is now running for the second year. The public series invites experts in different fields to discuss the historical development of a great variety of legal issues of interest to the Greater China region.

Amy L.

This article was originally published in No. 534, Newsletter in Mar 2019.