One Heart, One Way

Li Lianjiang survives academia

During his four-year undergraduate study, Li Lianjiang had been poring over two works: The Complete Works of Lu Xun and The Story of the Stone. Now and then, he remembers which pages certain scenes fall on, how the paragraphs begin and how they appear on the pages.

Which parts in The Story of the Stone did he go over from time to time?

‘I studied the psychology of Daiyu the heroine. Lin Daiyu is a typical loser—her sentiments towards the world and mine have a lot in common. She sees ill intents where there is none.’ The sentimentality of the heroine finds a sympathizer in the political scientist, because he feels he too is a loser.

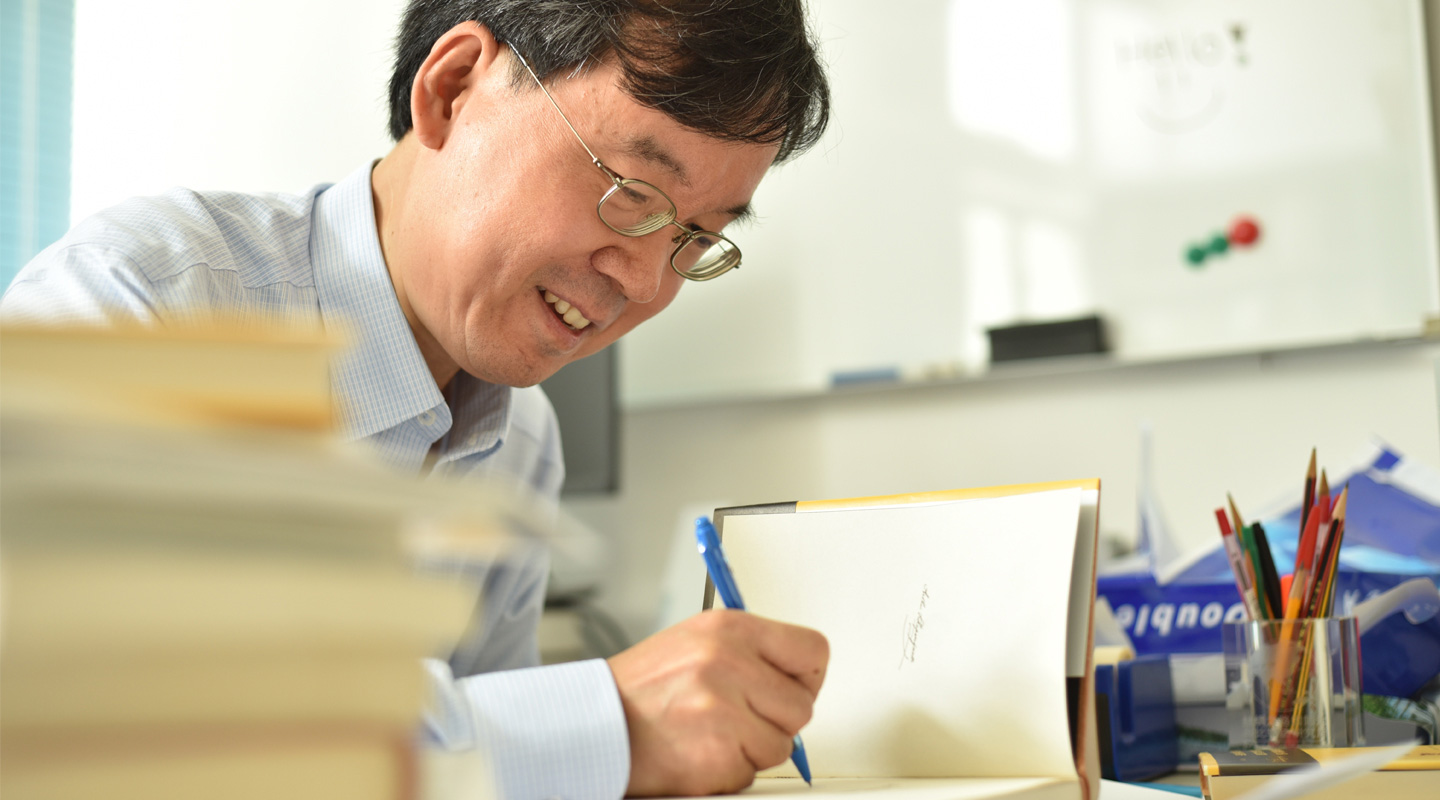

‘I am painfully shy and have stage fright. For over 20 years, I have set a record which no one can break: I never overrun.’ Not used to voicing his thoughts, the professor in the Department of Government and Public Administration feels at home spilling ink. Four years ago, the established Chinese scholar in international China studies made a comeback to the Chinese publishing world, publishing since then prose works on scholarly work and academic knowhow: Publish or Perish, Surviving in Academia, A Frivolous Discourse on Statistics: Quantitative Methods for Arts Students and Sequel to Frivolous Discourse: Putting Quantitative Methods into Use. The four works, amassing an enthusiastic following among research postgraduates, fill a blank in academic publishing: the scholar himself and how he carries out his work are conspicuously absent in academic discourses. The veteran scholar, having tasted the toil and tears of scholarly pursuit all his life, had his heart set on penning what he had been through. Most importantly, his sensitivity and disarming expressiveness make him the most suitable person to take up this herculean task.

Academic Work is Extreme Sport

‘Writing is an invariably frustrating exercise—you always need to surpass yourself. A scholar is not to repeat his own words. A viewpoint can only be expressed once, and every time you need to outlast your previous selves. In this eternal loop, you get a sense that you are not intelligent enough, feeling invariably helpless and hopeless. This is the toughest bit about academic work.’ Scholarly labour consists in writing, and writing is an extreme sport. A remark by his doctoral supervisor Kevin O’Brien hits the nail on its head: doing research requires one to ‘work to his incompetence’. ‘It is only through atrocious polishing that essays deemed to contribute ingenious understandings to the discipline can come out.’

The Serpentine Trajectory

Born in China in the early sixties, Li has a bureaucrat father and a peasant mother. A year before he was born, his father was re-deployed to a rural village, hence he was born a peasant. ‘The trials and tribulations of village life are beyond description; you must go there to actually learn how hard it is.’ To get water from a well, one has to hook the buckets onto a yoke and lower them into the well. A bucket of water weighs 30 kilogrammes. That means 60 on your shoulders when you take the water home. Li admitted he wasn’t able to do this. ‘Living in the village I cannot even draw the water I need to survive.’

The youth who knew well he couldn’t survive in village found his refuge in reading. The volumes he could get, however, were far from the best. ‘An everlasting regret it is. Our golden years for reading span around 10 years: from Primary 5 or 6 to senior secondary, one reads for pure joy, like a sponge taking up the liquid readily. When the sponge is fully soaked, the liquid, whether salutary or stinky, cannot be entirely expunged.’

In 1978, Li graduated from high school and attended the college entrance exam. The teenager from a rural village became one of the 400,000 college-goers from a pool of six million exam-takers that year. In October, he took the train to Tianjin to report to the Philosophy College at Nankai University, striking out a new path for his life.

At university, English, not philosophy classes, was the source of constant anxiety and anguish. From the outset, the 14-year-old who had hardly learnt ABC had to read English texts aloud in class with some 70 classmates. ‘Some of them had learnt English for three years, some for four or even six years.’ Obviously by far the youngest in the class, he was often picked by the teacher to answer the questions. Looking stupefied and unable to utter anything coherent, he felt embarrassed and pained. ‘You are young and will catch up with us in no time.’ His classmate’s word of encouragement lifted him from the depths of despair. He listened to English radio programmes and cassette tapes, translating Armand Maurer’s 300,000-word Medieval Philosophy. In Year 3, he was the one with the highest proficiency in English in class.

In 1990, Li headed to the US to read politics at The Ohio State University which he had got acquainted with via the Fulbright Program. In 1992, his teacher Kevin O’Brien was invited by the Chinese government to observe village committee elections in China. Based on discussions with his teacher and reading the literatures he brought back, Li devised his doctoral research around village committee elections. In 2006, he and O’Brien published their co-authored Rightful Resistance in Rural China.

Breathing the Airs of God

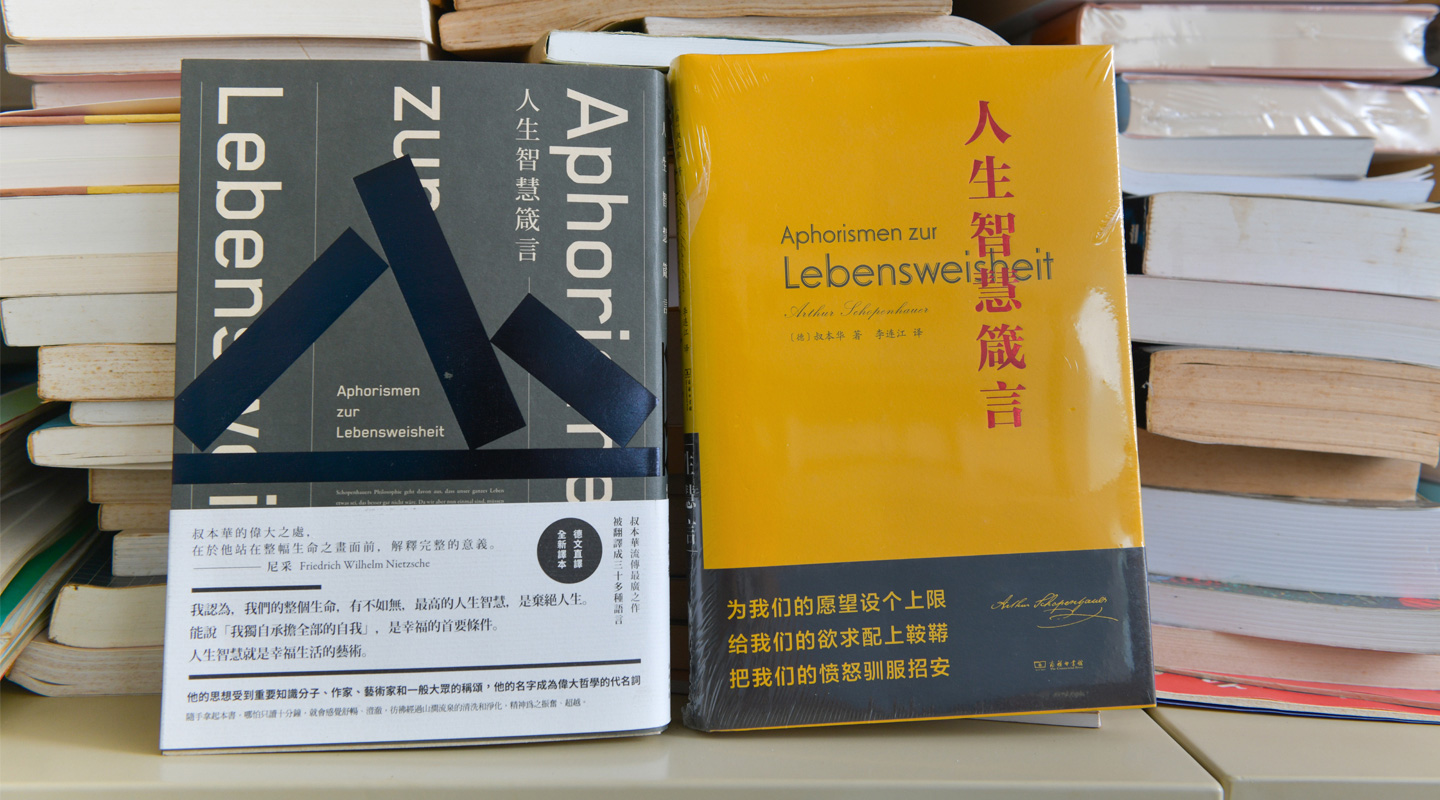

In Li’s mind, since he was 50, no philosopher has given him more inspiration than Schopenhauer. His Chinese translation of Aphorismen zur Lebensweisheit—in English Aphorisms to the Wisdom of Life, published in 2017 and the latest addition to his corpus of translated works totalling three million words, is the one work he believes will stand the test of time.

Why such a fondness for Schopenhauer? ‘What is so respectable about Schopenhauer is that he can talk familiarly with you like an old man does, elucidating profound philosophical insights with plain, figurative language. Most philosophers cannot bear keeping things sweet and simple, for they want you to hold them in awe, viewing them as demigods. This book is a pill for the young, liquor for those halfway through their lives, and tea for the old and seasoned. The young take the pill for their grow-up pains and anxieties for the future. Those in their midlife need spirits for that blissful forgetfulness. For those nearing the end of their lives and having done all they have to do, they’d need this book to sip and savour their past. Pill, liquor and tea are my takes on Schopenhauerian philosophy: it is an apothecary that gives whatever you want.

‘That Aphorismen has been in print for 160 years and translated into more than 30 languages is strong proof of its enduring stature. By bringing Schopenhauer into the world of the Chinese, I made him part of our enduring Chinese culture. I am bringing the enduring values of the Chinese and the world together, and in the process become a part of both.’

The Crooked Neck Tree on Stony Cliff

Last year, for his sabbatical, Li Lianjiang went to Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences as a visiting scholar. On the knoll opposite the Stanford golf course overlooking half of the campus, he had meaningful exchanges with the world’s finest scholars in different disciplines and had his mind blown wide open. During his six months there, he wrote a new research proposal and was approved grants from the Research Grants Council. ‘Suddenly the path has widened. Like walking from the University Station to the University Administration Building, you feel there’s no way to go; but looking up you’ve still got New Asia College.’

Li believes in destiny and knows his calling: scholarly life and life itself are finite and hemmed in. Preparing for the worst, hoping for the best and doing his utmost, he refuses the temptation of resignation and instead proactively takes part in shaping his own fate.

‘I am a crooked neck tree on a stony cliff. The seeds having landed in the muddy cracks, I was given a chance to grow. But my roots do not reach deep; it is impossible for me to grow into an expansive canopy. I stoop low when there are rocks touching my crown; I tilt to one side when there are hindrances left and right. My conviction is that man must do something for his place on earth, the way plants must vie for sunlight and produce oxygen through photosynthesis. All these years I do whatever I can, and do them with all the strength of my will and soul.’

The honest scholar lives up to what he claims.

By amyli@cuhkcontents

Photos by amytam@cuhkimages and ponyleung@cuhkimages