Deposing the Emperor of All Maladies

Patrick Tang invents novel virus-free gene therapy to treat cancer

Cancer.

The emperor of all maladies, the king of all terrors.

Few things strike more fears into the hearts of people than the very mention of this six-letter word. As delineated by Siddhartha Mukherjee in his Pulitzer-winning book, cancer is commonly regarded as the defining plague especially in recent human generations—back when he published his tour de force in 2010, it was estimated that one in two men and one in three women in the US would develop cancer during their lifetime.

Cancer has haunted human civilizations for as long as we know. In fact, dating back to as early as 3,000 B.C., Egyptian surgeons had already documented the first case of cancer in the Edwin Smith Papyrus, calling the sickness ‘incurable with no treatment’. Henceforth, humankind has embarked on a journey to study, understand and unshroud the fatal illness with one goal—to eradicate the disease and end its tyranny once and for all.

‘Cancer is still an active killer worldwide to this day. In Hong Kong for example, cancer accounts for about one-third of total deaths in the last two years,’ said Prof. Patrick Tang of the Department of Anatomical and Cellular Pathology. ‘Seeking the perfect panacea for cancer is a formidable task. Nevertheless, no difficulty is truly insurmountable if we set our minds to it.’

When talking about expertise and research experience in combating cancer, Professor Tang is definitely a force to be reckoned with. After finishing his postdoctoral training at the University of Oxford on primary drug resistance in cancer, he joined CUHK in 2014 and has since dedicated much of his academic career to studying cancer gene therapy and tumour microenvironments, publishing more than 50 research papers on renowned journals such as Nature Communications, Nature Reviews Nephrology, PNAS, Molecular Cancer, Molecular Therapy and Cancer Immunology Research.

‘Gene therapy is an emerging field of cancer treatment and makes use of genetic material to modify our body cells. For instance, we can tailor a specific gene and introduce it to cancerous cells to slow their growths, or transfer genetically modified immune cells to destroy tumour cells,’ said Professor Tang. ‘Comparing with traditional treatment methods such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, gene therapy offers higher specificity and causes fewer side effects to the human body.’

This treatment, however, comes at a price. ‘The practice of conventional gene therapy has raised safety concerns particularly in clinical setting as it often utilizes viral particles for the treatment.’ explained Professor Tang. Indeed, doubts about the safety of gene therapy had reached new heights when researchers from the University of Pennsylvania concluded that injection of adeno-associated virus 9, a virus that is used in gene therapy and normally considered harmless, can cause severe liver and neuron damage to animals.

This gives Professor Tang an idea: is there any other way to free the gene therapy from safety issues? Is it possible to deliver the treatment without using any virus?

Therefore, he collaborated with Prof. Lan Hui-yao of the Faculty of Medicine and Prof. Li Chunjie from Sichuan University and initiated the ‘Virus-free Anticancer Gene Therapy’ project in 2018. Joining forces with Prof. To Ka-fai and Dr. Xue Weiwen Vivian of the Department of Anatomical and Cellular Pathology, the team successfully invented a novel virus-free method which can specifically target any pathogenic gene to inhibit cancer.

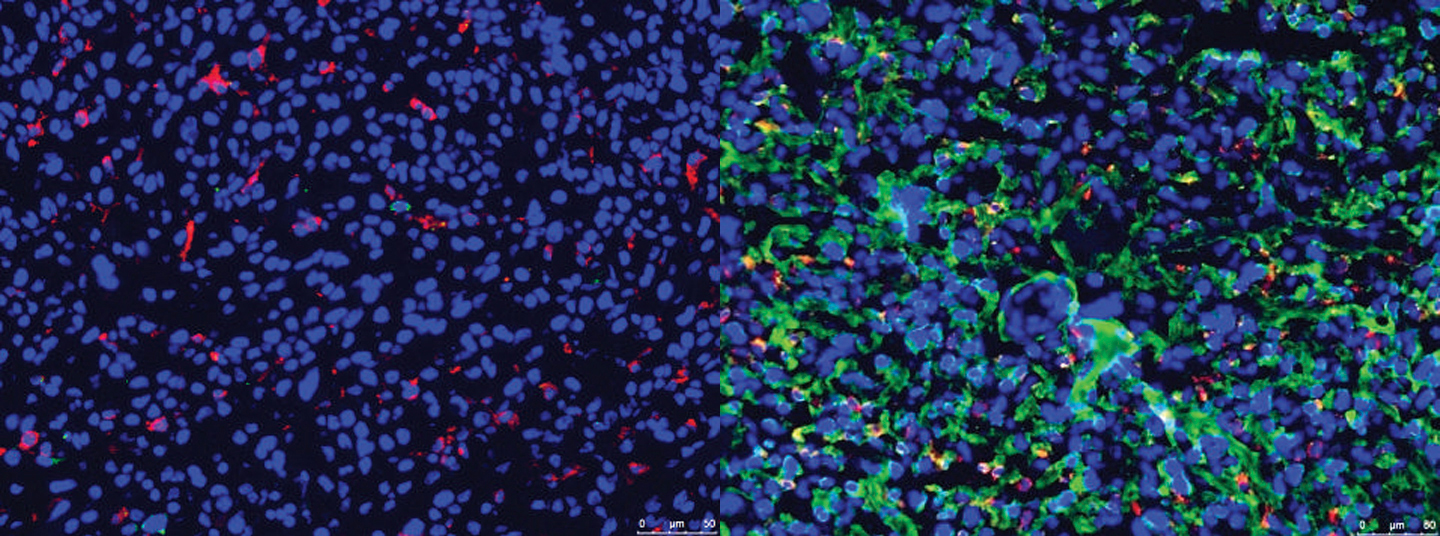

This is how the virus-free gene therapy works: the team will first customize and construct a genetic modifier called ‘short hairpin RNA-containing plasmid’, an artificial molecule that can cancel human gene expressions and is capable of inhibiting a specific cancer. Upon ascertaining its effectiveness, the team will mass produce the genetic modifier and release it into the tumour cells through an ultrasound-mediated microbubble system. In the end, the genetic modifier will gradually degrade in human body without affecting the inherited DNA of the user.

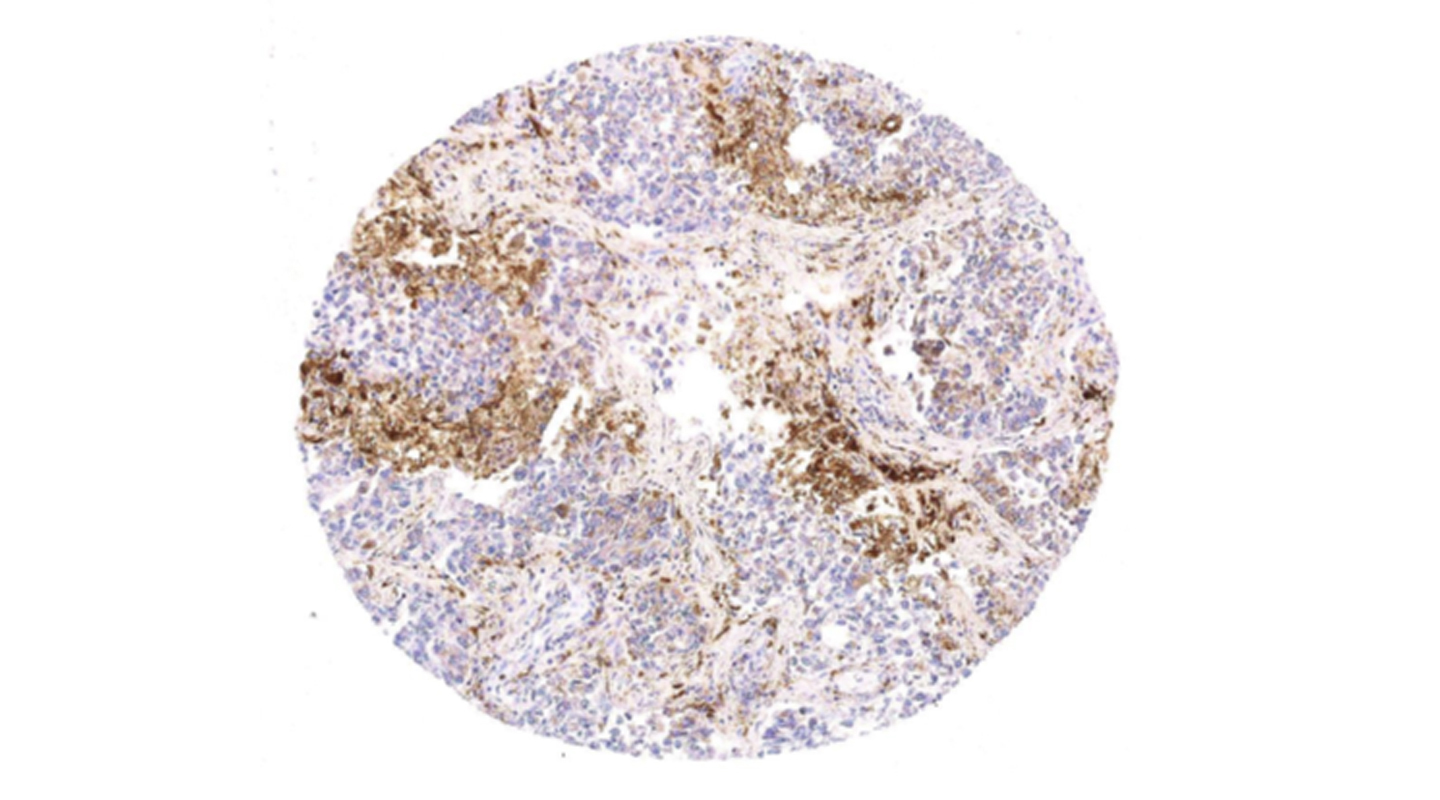

To better explain the theories behind, Professor Tang gave an example, one which also demonstrates how powerful the virus-free anticancer therapy can be in terms of therapeutic efficiency. ‘In one of our recent studies, we found that Mincle, a lectin receptor that detects bacterial infection, can significantly accelerate the progression of lung cancers and is normally associated with the mortality in those patients. We also learnt that the pertinent tumoural activities are promoted most actively in a location, the Mincle/Syk/NF-κB Signaling Circuit in tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs).

‘By utilizing our gene therapy, a specific genetic modifier can be customized so that it can silence and prevent Mincle’s activities from taking place in the Mincle/Syk/NF-κB Signaling Circuit in TAMs, thereby inhibiting the cancer progression successfully and accordingly.’

The perks of practising Professor Tang’s therapy are many. Most salient of all is the safety that the new method has brought about and assured. ‘With our virus-free anticancer therapy, users would not have to worry about the viral complications observed in conventional gene therapy,’ said Professor Tang. ‘Every gene has its physiological function which should be preserved and left unaltered. The beauty of our invention is that it will not permanently rewrite or damage a patient’s genome DNA. If users choose to use our method, they can maintain a healthy constitution and vigorous bodily functions.’

Besides overcoming safety concerns, the novel virus-free gene therapy also shows promising results in preclinical studies. ‘We have evaluated the anticancer effectiveness of our new method on mouse models with various cancer types, including melanoma, lung carcinoma, hepatoma and breast cancer. Upon analysing the test results between control and experimental groups, we found that those which used virus-free gene therapy for cancer treatment show 80% more tumour shrinkage than those which did not,’ Professor Tang expounded.

The findings made by Professor Tang have won him prestigious awards, including the young investigator awards in ISN Frontiers Meeting 2018 (Tokyo) and East Meets West Symposium 2018 (Hong Kong), as well as Faculty Innovation Award 2019 from CUHK Medicine.

The future looks bright indeed. Professor Tang is now actively looking for collaborations with biotech and pharmaceutical companies in hopes of expanding the application of the treatment to cover other cancer types and human diseases.

‘We are also seeking additional funding to solidify this new anticancer therapy,’ he said. ‘After all, the process of translating experimental discovery to clinical therapeutic is costly and timely. Nevertheless, we are still optimistic and would try our very best to perfect our project and help cancer patients.’

Currently, the virus-free gene therapy project is funded and supported by the Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Fund of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Research Grants Council, the State Key Laboratory of Translational Oncology, and also the Direct Grant for Research of CUHK. The team has filed a provisional patent in both the US and in Hong Kong.

From primitive radiation and chemotherapy to the virus-free gene therapy we see today, humans have made huge strides and breakthroughs in cancer treatments. Although the ultimate elixir is yet to be found, those who are affected by cancer—patients and their loved ones alike—should never lose hope and the will to survive.

‘My father passed away when I was two years old due to kidney disease complications. Losing a loved one is hard, but always remember that there is always a rainbow after the rain. Keep moving forward with a smile, and when you look back, you will realize that life is a beautiful and wonderful thing.’ Professor Tang ended the interview with a few therapeutic words.

By ronaldluk@cuhkcontents

Photos and visual design by amytam@cuhkimages