CUHK Radiologist Uncovers Relationship between Balance and Scoliosis

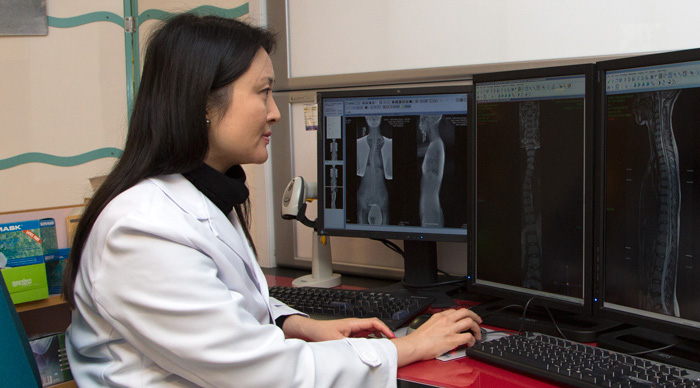

Prof. Winnie Chu

Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology

It's her role as a mother of two that put radiologist Winnie Chu on the course towards ground-breaking discoveries in the condition known as scoliosis. Professor Chu has uncovered a previously unknown relationship between the inner ear, the brain and the spinal column that causes previously healthy girls to suddenly begin to develop an abnormality in the shape of the spine.

Scoliosis, or curvature of the spine, affects around 4 per cent of the population worldwide. Most commonly, it afflicts adolescent girls, with onset between the ages of 10 and 16. Most patients develop scoliosis with their spine forming an "S" shape. The reverse form – with the letter backwards – is rare.

"My girl is not yet at adolescence, so she could have it," Professor Chu says. 'Whenever I see a patient I say, "If I were the mother of that child, what would I want to know about it?"'

Previous medical theory suggested that scoliosis only affected the spine, and the vertebrae that make it up. But Professor Chu has found that the condition also involves "anomalies" in the brain and the semicircular canals of the ear, as well as the spinal cord inside the spine. The spinal deformity is simply the most visible symptom of the disease, while there are numerous "hidden" features that have yet to be fully explored.

It was happenstance that Professor Chu came across her findings. She was initially examining the lung function of patients with scoliosis, and as a result also had images of the spine. She started to examine them as well, to supplement her information, and how the spine affects lung performance. The deeper she delved into the topic, the more she became fascinated with the theory surrounding the cause of scoliosis, and began examining the spinal cord itself, as well as the brain and then the systems of the ear.

She became convinced that the nervous system was involved in causing curvature of the spine. By studying the parts of the brain that are concerned with how the body balances itself, she realized scoliosis patients had an asymmetry in those systems that potentially throws them off balance.

Such a relationship had been posited in academic papers and conferences, although it had yet to be confirmed clinically. "I listened to the discussion and I thought it sounds reasonable. But I am the one to prove it," Professor Chu says.

X-ray technology has yielded images of the spinal structure for more than a century. But it examined just the bones and the shape of the spine. It's only through advances in magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, that it has become possible to scan the activity of the nervous system and spinal column in any great detail. Professor Chu has now developed a large database of MRI information from her clinical practice treating scoliosis patients at Prince of Wales Hospital.

"The advance of imaging techniques is still evolving," Professor Chu, who holds a post in CUHK's Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, says. "Before we could only look at the morphology and the shape. Now we can look at the function, and look inside the nerve fibres."

It was also previously very difficult to study the vestibular system, the inner ear, in any great detail. Whereas the spinal column and brain develop extensively after we are born, the vestibular system changes very little after birth.

Professor Chu now believes that it is likely scoliosis begins with an imbalance in the inner ear, which governs how we keep our balance. In scoliosis patients, the inner ear rotates on slightly different axes from normal, and the shape of the inner ear is different. That results in the system not being as effective as normal, resulting in a slight loss of balance, Professor Chu's work shows. With the body not in its correct posture, the imbalance eventually leads to curvature of the spine.

The girls are healthy in all other ways, although the misshapen spine affects their movement. When the deformity is dramatic, it often affects a girl's self-confidence and can make them self-conscious about exposing their spine, meaning they will refuse to take part in activities like swimming.

The cause of the disease had previously been a mystery, although the fact it recurs in certain families, and targets females in particular, suggests there's a large genetic component. It's also possible that, since girls are more slender and often taller than boys in adolescence, it is a byproduct of growing spurts that leave the body unable to handle the rapid growth of the spine.

To treat scoliosis, patients often have to wear a thick corset that helps straighten the spine, but also restricts movement. At its most invasive, scoliosis is treated with surgery, and a titanium rod is inserted into the back to anchor the spine. "This is the final treatment, but nobody wants to go to that extreme," Professor Chu says.

If Professor Chu's theory about the effect of the inner ear proves correct, it's possible that training the patient to strengthen their balance would prevent scoliosis, or curb its severity. An improved understanding of the origin of the disease could also lead to better screening to identify at-risk girls, and the chances of how severe the condition will be.

"We want to have preventative treatment, and know the progress: will it be severe, or can I enjoy my life normally? Is there anything I can do to prevent it progressing?" Professor Chu says. "There are still a lot of things to explore."

By Alex Frew McMillan

This article was originally published on CUHK Homepage in Apr 2014.