Saving One of China’s Symbols: CUHK biologist’s research helps replenish species

Prof. Wei Ge

School of Life Sciences

The survival of one of China's most emblematic animals depends on the study of a "virus with a backbone", a fish that replicates unusually fast. Besides the panda, perhaps only the Chinese sturgeon best represents the national psyche, considered a national treasure.

The critically endangered fish used to be plentiful in the Yangtze River and along the Chinese coast. But overfishing, pollution and the construction of several large dams have decimated its population.

It is through intense examination of the zebrafish, a small, fast-breeding species, that Prof. Wei Ge of the School of Life Sciences has unlocked the precise way that an animal's cells communicate and instruct each other to start puberty and begin to reproduce. That will prove a key factor in helping the sturgeon's ongoing existence, and help in farming the fish as well as reintroducing fry to the wild.

Sturgeon grow well in captivity. But younger fish simply don't become sexually mature, and that means they can't reproduce. So at the moment, there's no way to cultivate fish for reintroduction into the wild through a captive breeding programme.

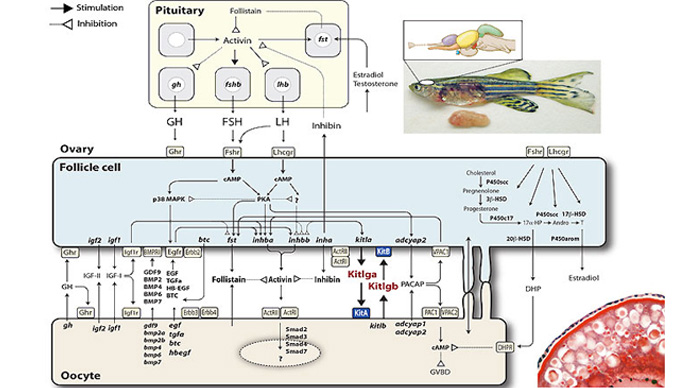

It is thanks to Professor Ge's unique insight into the zebrafish that he has been able to develop an understanding of the reproductive process that can lead to a successful sturgeon breeding scheme. Biologists from Australia, India and China have come to his laboratory to learn how to replicate his unique technique of micro-dissection of the zebrafish's reproductive system, and the work has been published in the preeminent journal in the field, Molecular Endocrinology.

By separating the somatic cells – the body's normal building blocks – from the oocyte, or egg, it's possible to examine how they interact. That tells biologists what it is that begins the reproductive process.

"We use forceps and just peel the somatic cells off, which are barely visible. You really have to go on your gut feeling," Professor Ge says. "After you separate those two you can decide which cells are doing what, and you can understand the communication between the cells."

Biologists have known since the 1960s that body size determines when a human begins puberty, with larger people becoming reproductive earlier. The same was also obvious in other mammals. But nobody knew why.

Humans and other large species take too long to grow to sexual maturity for scientists to study them. But zebrafish, no bigger than a goby, are a "virus" that spreads very fast – females breed each and every day, spawning about 100 eggs every time, all year round. Their fecundity and short life cycles make them perfect for the study of reproduction, and the reproductive axis, Professor Ge's speciality.

Professor Ge's zebrafish examination discovered a protein, known as YB-1, that plays a critical role in the timing of the onset of puberty – when it is present, puberty can't start. He has found that the protein is controlled by a hormone, IGF-1, which helps get rid of YB-1, allowing puberty to start. That insight helps understand how the breeding process begins.

"If we want to activate an egg, you just find what controls those proteins, and then you can control the onset of puberty," Professor Ge says. "If we can understand this fundamental phenomenon we can apply this process to aquaculture."

Professor Ge has been asked to participate in a programme in Wuhan that will, if it succeeds in its funding application, work on saving the Chinese sturgeon. By breeding the fish in captivity, it should be possible to develop fry that can be introduced to areas where the sturgeon has already died out, as well as to grow fish for eating, reducing the pressure on the wild population from fishing.

"When I present it at international conferences people really get excited about it," Professor Ge says. "There may be some other species in the future that might face the same problem that we could also help."

This article was originally published on CUHK Homepage in Dec 2013.