A Virtual Treasure Trove

The Special Collections of the CUHK Library help keep history alive

The official Hong Kong story starts from 1842, when the then fishing village was ceded to the British. Since then, Hong Kong has been a confluence point where different ideas and ethnic groups converge, as a result of which considerable quantities of valuable textual materials have found their way to this international city. The Special Collections of the CUHK Library, for example, have in possession a robust body of such materials, and they play an indispensable role in helping us trace the contours of Hong Kong’s cultural landscape.

Thanks to digitalization, the Collections are now accessible to both local and overseas viewers.

‘Our Digital Repository not only allows researchers around the world to see the texts and images as they are, but also contributes to a better understanding of Hong Kong’s culture through international scholarship,’ said Ms. Louise Jones, the University Librarian.

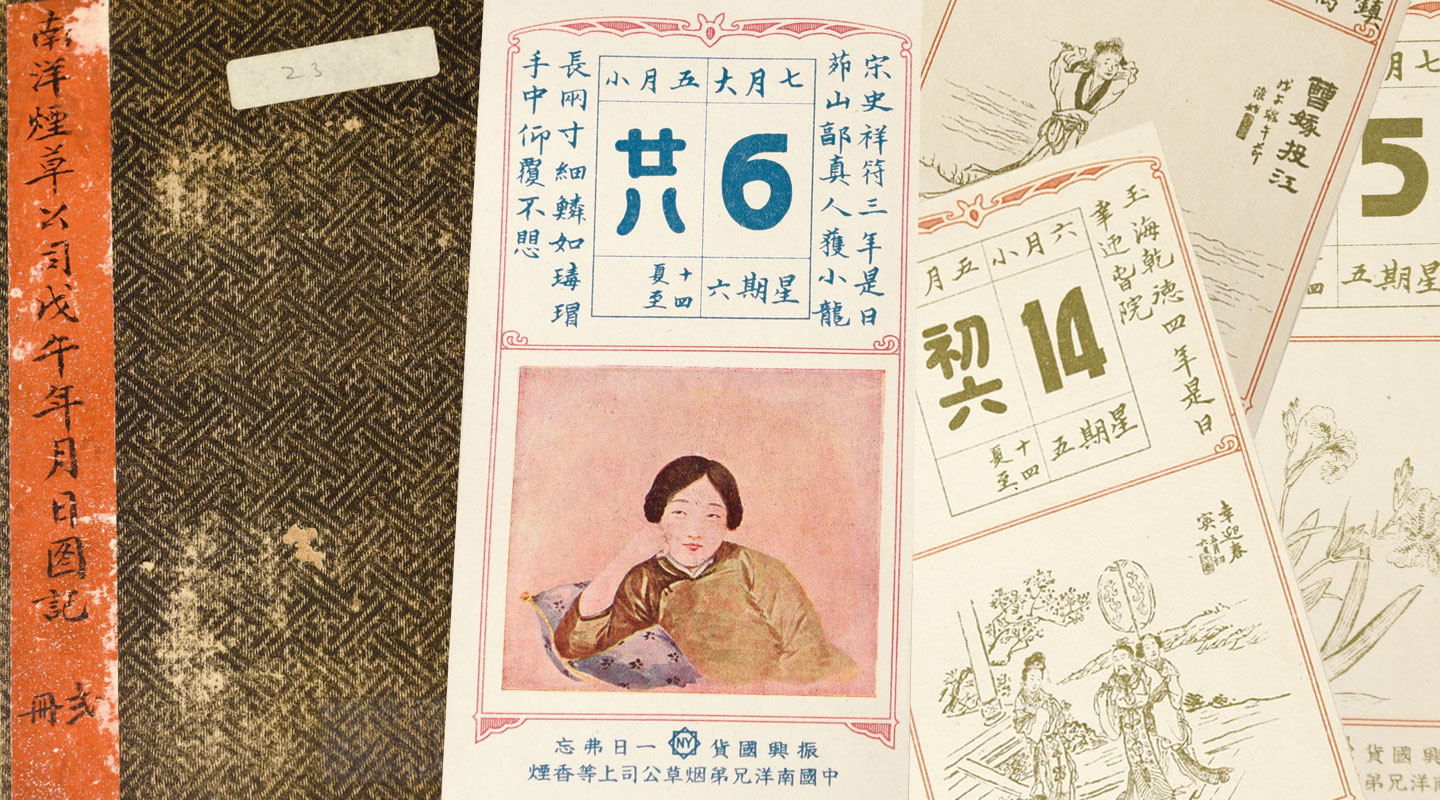

The digitalization initiative, spearheaded by the Research Support and Digital Initiatives of the Library in 2015, has led to the establishment of the CUHK Digital Repository, from which the archived materials of the Special Collections can be searched and viewed. According to Ms. Li Lai-fong, head of the Special Collections, the Library has in place a set of regulations governing the digitalization process. For example, ancient texts at greater risk of deterioration are given priority. At present, all woodblock print books from the Ming Dynasty (mid-14th to mid-17th century) have been digitized. Other examples include a collection of ancient texts on traditional Chinese medicine and calligraphy and paintings from the Qing Dynasty. Researchers, as well as the lay public, can in the comfort of their homes log onto the Digital Repository to leaf through rare books dating back to the Ming Dynasty. The convenience offered by the Digital Repository not only promotes the dissemination of knowledge, but also enhances CUHK’s reputation as a centre of learning.

However, the Repository only represents a fraction of the holdings of the Special Collections. To examine materials inaccessible online, users must pay a visit to the Special Collections Reading Room inside the Library.

‘Some donors may not wish to have their letters, scripts, or images made available on the web. Whether an item is eligible for unfettered public viewing or not is guided by the donation agreements signed,’ Ms. Li said.

Most of the archived materials are donations from collectors, scholars, and public figures who are associated with CUHK or who identify with the University’s tradition in the humanities. There are many factors affecting owners’ decisions as to where to donate their personal archive and library. ‘Donors prefer beneficiary organizations which can guarantee the conservation of their acquisitions. They are also more likely to donate to organizations they are familiar with or recommended by someone they trust,’ Ms. Li explained.

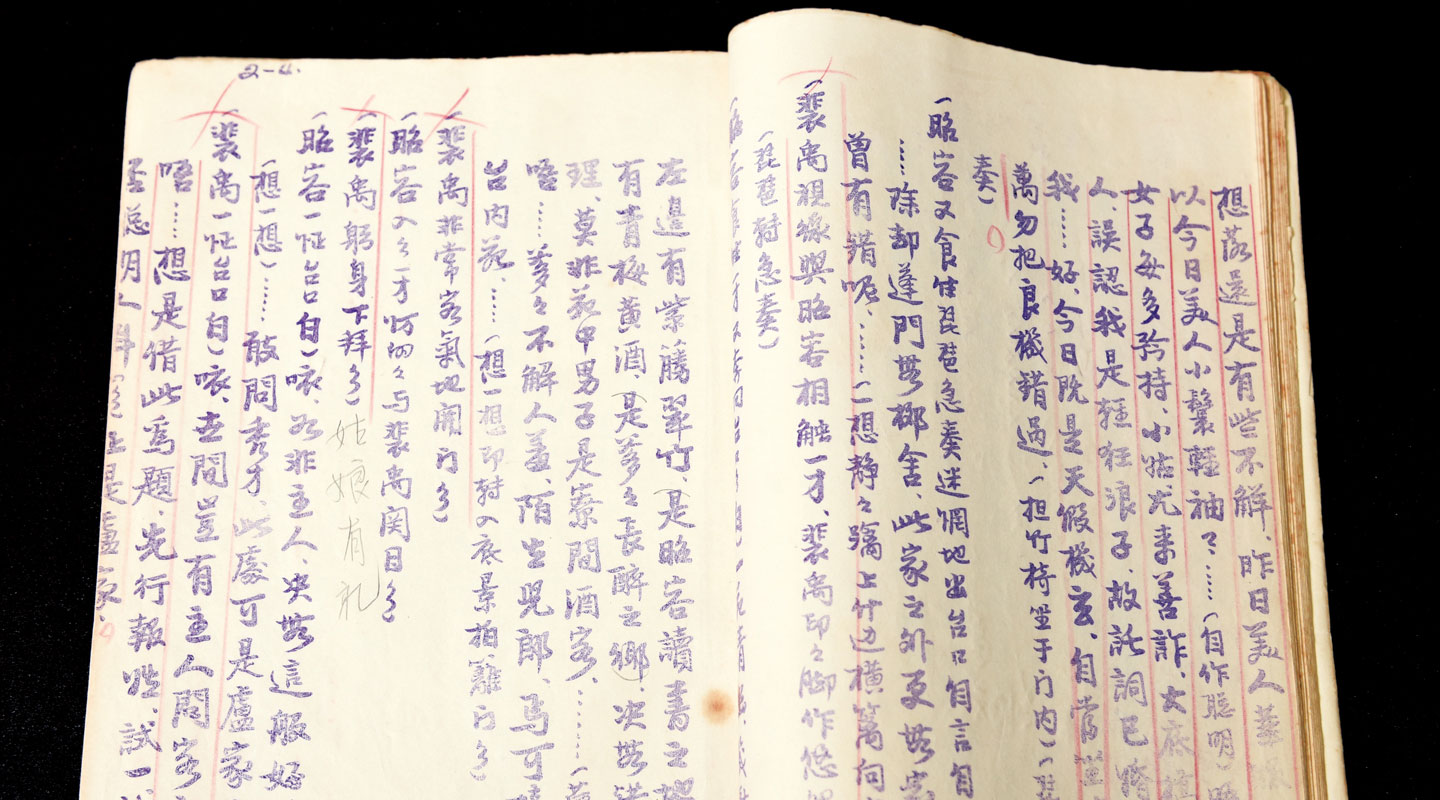

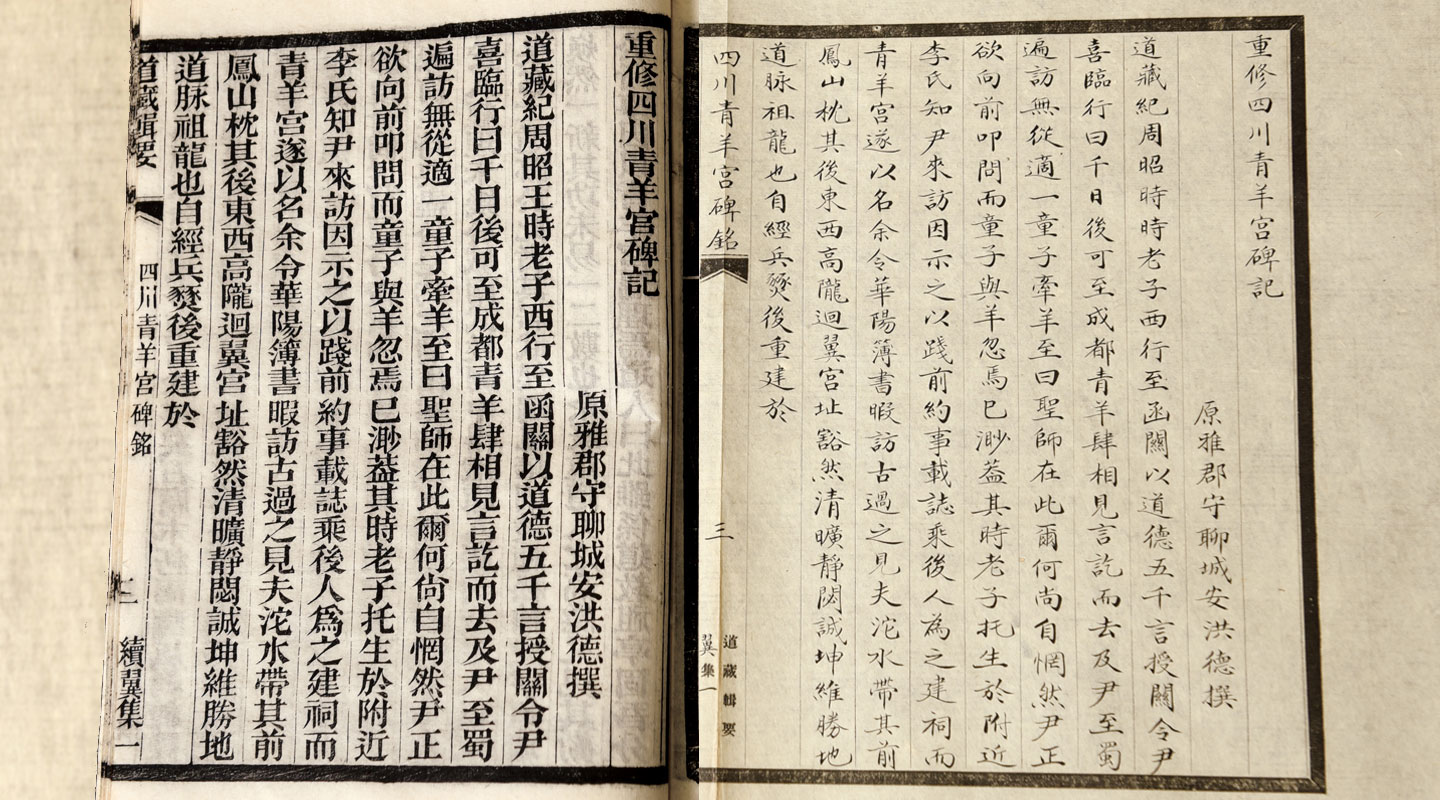

When asked if there were any donation stories she could share, Ms. Li spoke of a woodblock print anthology of Daoist texts and a matching manuscript, which was supposed to guide the engraver throughout his work. The manuscript was donated by Prof. Ma Mong, a renowned scholar of Chinese studies, while the woodblock print book was previously owned by a monastery in Chengdu, Sichuan. What is particularly remarkable is that the two books were acquired from different sources, and it seems that destiny somehow had worked to bring them together after a long separation. Both the woodblock print text and manuscript describe the renovation of a Daoist monastery in Sichuan province in the late Qing period.

Apart from online and on-site viewing, the archived materials are also displayed at regular themed exhibitions. ‘Daoism Outside/Inside: An Exhibition on Daoist Scriptures and Ritual Texts of the Qing Dynasty’, held from March to July 2016, had on display prayer books, biographies of prominent Daoist monks, and books on Daoist medicine. It is worth noting that the exhibition, which was open to public, was co-organized by the Centre for Studies of Daoist Culture and the Library.

In working with academic departments and university stakeholders on themed exhibitions, the Library helps promote the University’s role as a curator of knowledge.

‘In fact, external organizations such as the Hong Kong Museum of History sometimes borrow artefacts from the Collections. Such collaborations present opportunities for the Special Collections to work with and for the community,’ Ms. Li said.

The scope of the Collections’ holdings is not limited to subjects related to traditional Chinese history and culture. The Collections have in possession a wealth of manuscripts, scripts, letters, and books by writers who are either based in Hong Kong or once resided here, such as Liu Yichang, Lo Wai-luan, and Yu Kwang-chung. As for researchers and students interested in local history and politics, they will benefit from the Collections’ government documents and archival materials related to public administration and civic engagement, including proceedings of meetings, annual reports, magazines, and documents of NGOs and Chinese ethnic associations.

When asked what subjects are most popular among library users, Ms. Li said, ‘CUHK researchers and teachers are mostly interested in rare books and books published in the Republican era, while the undergraduates favour Hong Kong studies and history.’

The Special Collections are open to students and researchers from other local and overseas institutions. At present, about 75% of the Collections’ users are members of the CUHK community.

The appeal of the holdings to users on and off campus certainly justifies the efforts the Library has spent on the creation and maintenance of the Collections. What is truly special about the Special Collections is its accessibility to those who attempt to glean from the vestiges of the past the inspiration for tomorrow.

This article was originally published in No. 486, Newsletter in Nov 2016.