Ever-fluid in Nature and Form

Frank Vigneron and Art

A Traveller at Two Homes

Prof. Frank Vigneron got his Chinese name 韋一空 (Wei Yikong) in 1998 upon the request of the gallery which held his first exhibition in Hong Kong. The Zen-like name was given by his Chinese wife who knows his work well. It literally means ‘one void’, voidness being an essential element in Chinese painting and philosophy.

Having a Chinese name may help a foreign artist in Chinese-speaking communities, but it brings more nuisance than convenience in daily life, like receiving a cheque payable to this name under which he has no bank account, or failing to check into a Beijing hotel room reserved under this name by an event organizer.

Vigneron’s father worked for a shipping company and had lived in England, Madagascar, and twice in Hong Kong. ‘I was born here, and then moved to Vietnam and Belgium, before moving back to France when I was nine. I was mostly educated in Belgium and France.’ With a PhD in comparative literature, he can read classical Chinese. He also received a PhD in Chinese art history from the Paris VII University and a doctorate in fine arts from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.

It was 1990 when, with only a working knowledge of Mandarin, Vigneron returned to his birthplace and began to discover the beauty in Cantonese and the robust local culture. He attributed his decision to stay in Hong Kong to his fascination with Cantonese.

Desert or Oasis?

Hong Kong used to be called a ‘cultural desert’. In Vigneron’s words, ‘It has never been farthest from the truth.’ He pointed to the enthusiasm in calligraphy and painting since the early colonial days and the vibrancy of the newspaper columns which yielded many serious writers. Its lack of art institutions was compensated for by the existence of galleries and museums. The Hong Kong City Hall, opened in the 1960s, was built with a museum.

‘That Hong Kong is a cultural desert is a platitude repeated by those who neither spoke the local language nor understood what’s going on here,’ he said. He also emphasized that as the colonial government exercised little control over art, Hong Kong artists had more freedom to explore a variety of arts in comparison to Taiwan and the mainland.

To Flip or to Keep?

Art education is now available in many places. But Vigneron thinks that the idea of professors being the source of knowledge is antiquated in the Internet era since students are often just as knowledgeable as their teachers. But ubiquitous information gives rise to false information. ‘To help the students select and make good use of the information, we still need teachers. This cannot be done by robots. We can adopt the idea of flipped classroom, create content, put it online and spend the contact hours on leading the students on their projects.’

The migration from chalk and talk to flipped classroom is resource intensive, however. Vigneron had spent months on a 15-talk video series on Western art theory and philosophy for L-Art, an online art education platform in China. He said, ‘Academic staff have to deal with, on top of teaching and guiding student projects, the pressures from research and impact assessments to keep themselves afloat by publishing. It’s understandable they sometimes would rather stick to the lecture and term paper format.’

Art vs Administration

Art and administration are usually considered antitheses. Vigneron, an active plastician himself who joined the Fine Arts Department of CUHK in 2004, has led the department for the second year with subtle detachment. ‘I’m not exactly a people person. When discussing departmental affairs, the person who's talking is in my eyes the department chair not me. Keeping this distance is important.’ He believes that good management helps teaching and learning, but modestly dismisses he has any. ‘You cannot tell a group of people each with his/her own ideas and personality what to do. I’m just here to put forward to management what consensus was reached in the department. Fortunately, I have a strong team of support staff to handle the nitty-gritty for me.’

Vigneron is the director of Rooftop Institute, an NGO working mostly with secondary school students in Hong Kong. Rooftop invites Asian and local artists, many of them graduates of the Fine Arts Department, to conduct artistic research and discussions on contemporary social and cultural issues. He believes that all forms of art are agents of emancipation and empowerment, and hence has made social engagement a way forward for the department. This summer the department will roll out a credit-bearing social engagement internship programme.

Comics will be a new feature to the department’s curriculum. ‘Comics has incredible varieties and possibilities that range from very amusing to deeply meaningful,’ said Vigneron. Starting September, a famous local comics artist Stella So will teach a studio course while Vigneron will teach comic book history with a focus on the creative aspect of contemporary comics. The department has also signed an MOU with ESA Saint-Lucin Brussels, which will bring Belgian art students to CUHK for a semester of exchange.

As he sees it, the contribution of the Fine Arts Department to the local art scene is enormous. ‘Until about 10 years ago, CUHK was the only tertiary institution in Hong Kong offering art-making as a major. So most of the original and successful artists tend to have graduated from this tiny, tiny department with an annual intake of not more than 30. I wish to offer more studio-based education to our students. But for the moment we have serious space problem.’

Positioning and Classification

With the possibilities in cultural exchanges multiplied by the super high speed of information transmission, the way art is made, thought and presented has greatly transformed. Globalization has made fluid or obliterated the boundaries of artistic territories. Artistic practices have become more diversified. Vigneron noted that today’s art students have not been shy in mixing into their works images, sounds and videos from all over the world to arrive at a distinctive style of their own. He found that artistic style and influence are not very helpful guides to contemporary works. The dichotomies of East/West, traditional/ contemporary and public/private favoured by art history and criticism tend to fall into over-generalization, polarization and exclusion, and hence are grossly inadequate for the dazzlingly eclectic creative energies today.

In place of the old mounds, Vigneron proposes a relational model based on the Piaget group. It places the public/private and traditional/contemporary not as dichotomies but as the two extreme points on two scales. By integrating these two scales into one system, he hopes it can make one see better the simultaneous presence of various art forms—including ‘native’ Chinese art, ink art, plastician art and relational aesthetics—that might seem antithetical but in fact are not.

For example, the use of Chinese landscape painting to connect people belongs as much to the province of ink art as to that of relational aesthetics. The works of Tsang Tsou-choi, aka King of Kowloon, whose artistic identity is constantly shifting in the hands of the artists and curators of Hong Kong—from his actual public inscriptions to all the curatorial experiments thus generated—could occupy several positions in this Piaget group.

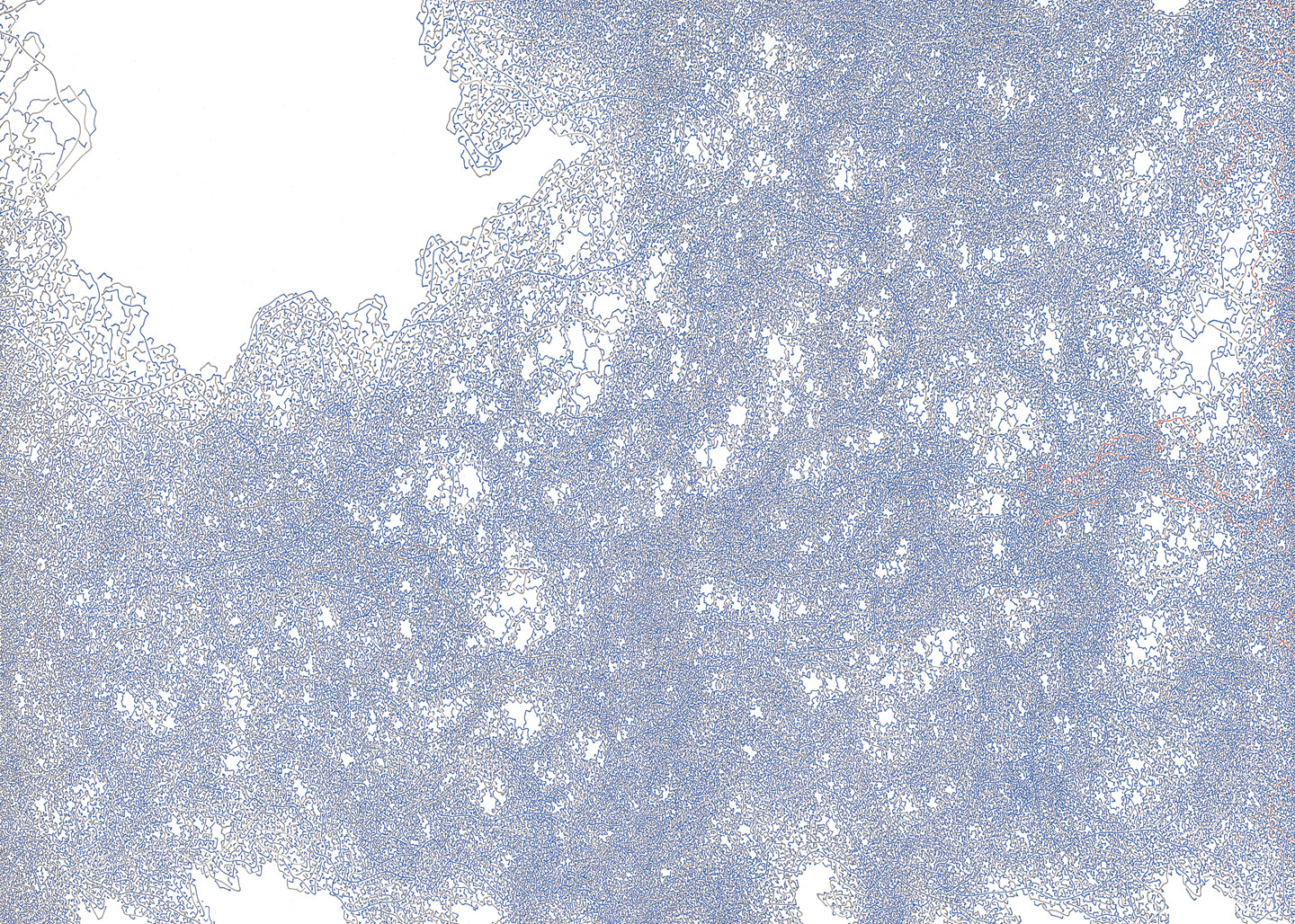

So, how should one classify Le Songe Creux, the series of works drawn by Vigneron with technical pens and which was exhibited in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Brussels as ink art? Vigneron described it as ‘a novel without a text, but still written with a pen on a table; images without meaning but are still divided into chapters.’ It should be closer to ’non-traditional (contemporary)’ and as a ‘private’ practice in the Piaget group.

Home or Diaspora?

There is so much more to positioning and classification than meets the eye. His mother tongue, his early years in northern France and his seven-year stay in Paris are his three French roots. But those roots have been left dry for some time. France is as remote as his last doctorate in 2008. He is hailed as a French artist in China. No such fuss in Hong Kong. Amazon labels him a Hong Kong artist. He may be as conscious of identity issues as the art galleries, but he has little clue.

S. Lo

This article was originally published in No. 537, Newsletter in May 2019.