Nominal Marriages

Susanne Choi investigates the compromising of sexual orientation with family obligations

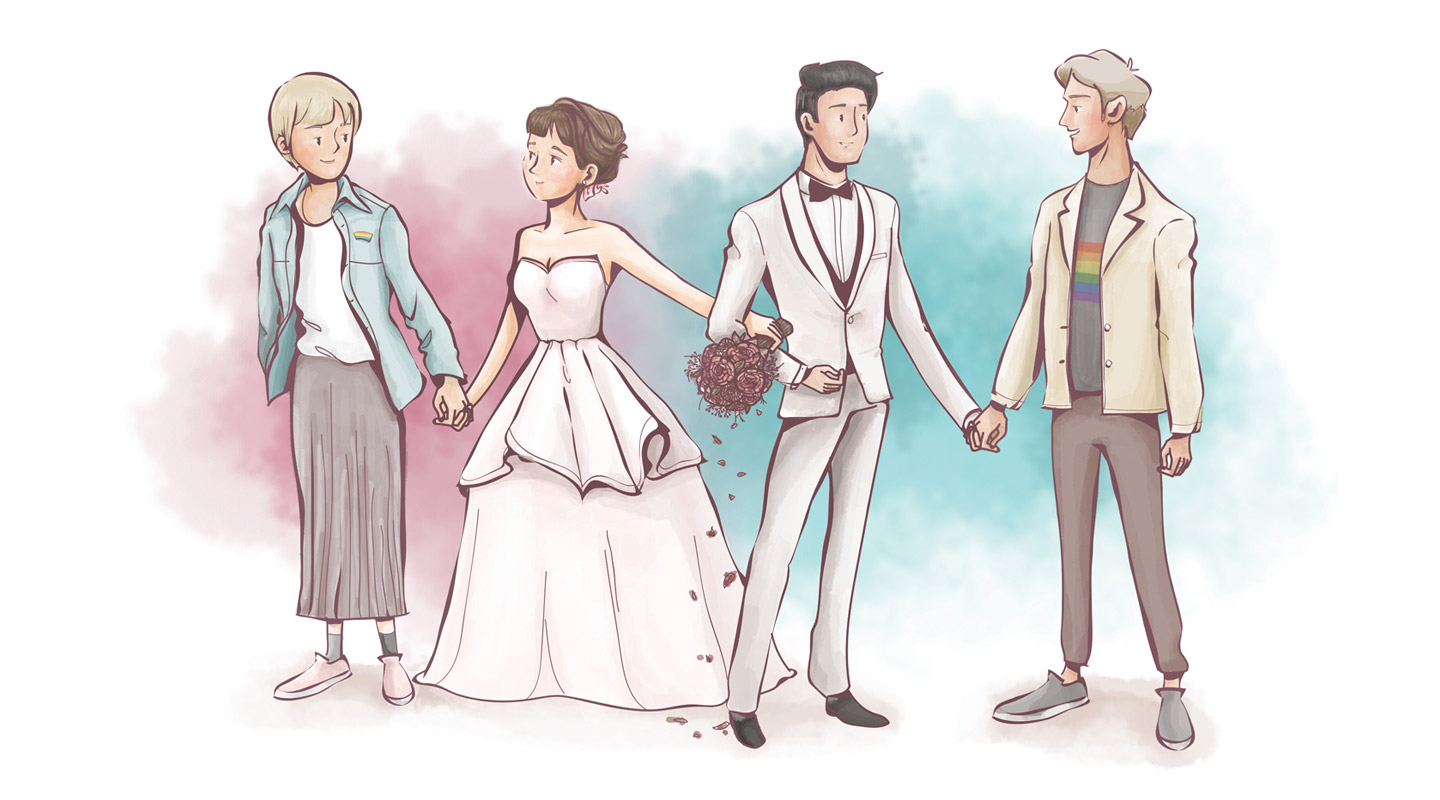

‘Nominal marriages’, employed as a front by gay men and lesbians in mainland China to appease their parents, remind us of the film The Wedding Banquet (1993) by Lee Ang. The film, set in Los Angeles, is about a Chinese gay man who tries to please his parents by marrying a woman, while maintaining a relationship with his American partner. After a drinking binge, the Chinese man has sex with the woman, who becomes pregnant with his son. The ending sees the gay couple and the woman raise the child together, offering a resolution of a sort to all parties involved.

But that note of optimism hardly seems to befit the reality faced by the gay men and lesbians who marry each other for the sake of convenience in mainland China, at least at present. In a joint study on nominal marriages, Prof. Susanne Choi of the Department of Sociology and her PhD student, Ms. Luo Ming, have shown how, in a rapidly changing China, sexual freedom is affected by the evolving role of family.

Their fieldwork started in a city in Northern China where gay bars and saloons abounded, and where there were also numerous NGOs serving the gay and lesbian communities, whom the researchers turned to for referrals.

‘We identified our interviewees through the NGOs, without whose assistance it would have been difficult for us to earn their trust,’ Ms. Luo said. Their interviewees were gay men and lesbians who drew up contracts to create a facade of heterosexual marriages to cope with parental pressure. They interviewed 14 gay men and 16 lesbians over a span of four years starting from 2010, as well as taking part in their social events. Their research has recently been published in the British Journal of Sociology.

Nominal marriages have attracted a lot of attention in recent years, and according to web-based surveys conducted in 2008 and 2009, ‘around half of the gay respondents had either contracted a nominal marriage or were looking for a nominal marriage partner.’ A quick Google search yielded a staggering number of 294,000 items on nominal marriages in 2014. In February 2017, that figure shot up to 820,000 items.

‘The Marriage Law of China stipulates that marriages should be a union between two willing parties, and that parents have no rights to force their children into marriages. Sex between men was once classified as a mental disorder, but such a definition of homosexuality was no longer valid when the Ministry of Health removed it in 2001,’ Professor Choi said.

Some people attribute the emergence of nominal marriages in China to a loosening legal grip on homosexuality; others interpret them as a clash between the Chinese family and the burgeoning individualism among the younger generation. While both explanations are valid, neither of them can by itself explain why nominal marriages prevail in mainland China, but not in other Chinese communities.

Professor Choi said that, in most Asian countries, a considerable proportion of homosexuals marry someone of the opposite sex as a camouflage to avoid parental pressure. In such marriages, the spouses learn about their partners’ genuine sexual orientation only some time after marriage.

‘We also see many people opt to stay single in places like Hong Kong and Singapore, and Hong Kong people are under less parental pressure to marry and produce offspring.’

In mainland China, however, being single and never married is a mark of disgrace, a subject of small talk by prying relatives and neighbours, much to the annoyance of parents. And contrary to the popular belief that economic development would go hand in hand with the rise of individualism, the hold of the family on the individual remains strong. Professor Choi and Ms. Luo believe that, as capitalism gains more ground, the safety net offered by the state economy has given way to financial and social instability. Many people therefore see the family as a bulwark against the uncertain world around them. Moreover, under the one-child policy, many parents and their children have developed a bond so strong that the children are willing to resort to nominal marriages to protect their parents’ feelings.

The growth of the Internet makes it possible for people of different sexual orientations to create their own ‘online communities’, where they can seek each other out and exchange information. The flourishing young middle class, who are better educated and live in cities far removed from their native homes, are more likely to opt for nominal marriages. As for the less affluent gay people living in rural areas, heterosexual marriages are often their only choice.

Nominal marriages might appear to be a trick pulled to fool parents, but some of these marriages are in fact accomplished with parental connivance. The researchers said some parents know that their children are gay, and accept nominal marriages as a way to defuse pressure from their social networks.

It remains to be seen whether nominal marriages could pave the way for more autonomy for same-sex couples. Nominal marriages represent a big step towards sexual and personal freedoms, taking into consideration the fact that male sex acts were branded as hooliganism two decades ago. That said, nominal marriages do reinforce the idea of heterosexual marriages. Some gay men enter into nominal marriages to continue the male line, a patriarchal custom at odds with gender equality. Requests of this sort are usually met with flat refusals by their lesbian partners, revealing the vulnerability of such contractual marriages. In such cases, a divorce is the likely consequence. Nominal marriages also draw criticisms for their lack of legal protection towards the contracting parties, and the mere fact such marriages may end up hurting the parents even more. The happiness that The Wedding Banquet promises is a far cry from reality.

The study on nominal marriages helps to trace the changes in the contours of China’s social and political landscape, and shed light on the way people make sense of their lives at the crossroads of sexual desire and family obligations. The choices of people in historical junctures will continue to bewilder and fascinate us.

This article was originally published in No. 493, Newsletter in Mar 2017.