How o’camp culture has changed and evolved with the times.

Reporters: Joana U and Stephanie Chan

Mention o’camps, or university orientation camps, in Hong Kong today and people might think of sexually suggestive games or groups of identically clad youngsters acting like cheerleaders in the heart of the city. But for Alfred Hau Wun-fai and his friend Au Yuet-ching, o’camp brings back memories of romantic midnight boat-rides across a tranquil lake in the 1960s.

Fast forward to the 1970s and the scene changes again, with students singing their college anthem and songs of the Chinese resistance against Japanese aggression and hotly debating the Cultural Revolution taking place on the mainland.

The nature of Hong Kong’s o’camps changed with developments in Hong Kong society itself and reflects changing expectations of the role of university students in society.

Alfred Hau joined the Chung Chi College (Chinese University of Hong Kong, or CUHK) o’camp in 1968 as a Geography major, while Au Yuet-ching was a Sociology freshman. It was a big event, a time to meet new friends and adapt to university life.

“Everyone joined, and so did I,” says Hau. He and Au are more than happy to recall their “‘antique”’ memories. They remind one another of episodes from the event and chuckle over them.

Hau says there were not many facilities on the campus in those days. They spent most of the o’camp in a stadium where games were held. Hau said that physical tests, such as running, were the most demanding. The students were also organized into teams which had to stage performances. This was the most unforgettable activity for him.

“At that time, most university students came from a number of elite secondary schools, so we [freshmen] were very united…we did not compete with each other at all,” say Hau.

Hau explains that students always shouted “cheers” to show appreciation of their fellow performers. This is unlike the slogans and rhymes, referred to as “dem beat” or “demonstration of beats” of today. Instead of appreciation, these contemporary rhymes may include personal attacks on the physical appearance or characters of members of other groups.

As for the nocturnal boating, Hau says rowing across the Tolo Harbour was a must-do and significant activity in the o’camp of the 60’s. A boy and a girl had to row on one boat as partners as it was deemed to be too dangerous and strenuous for two girls to row together. “Many lovers may begin like this,” says Au, grinning.

From romance to politics, the 1970s was a politically charged decade in Hong Kong. Au Yee-cheung entered CUHK’s History Department in 1972. He recalls that the o’camp of the day was less concerned with the internal affairs of student life on campus and reflected more of the social concerns, and especially mainland affairs, of the day. There was also a strong sense of common purpose, with students doing early morning exercises together and planting trees on campus.

By the 1980s, the focus was on Hong Kong’s political future. Britain and China were negotiating what would become 1984’s Joint Declaration.

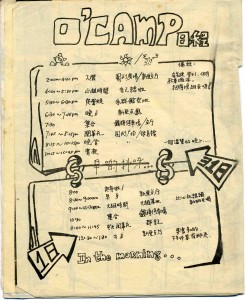

Allan Au Ka-lun joined the New Asia College o’camp of CUHK in 1986. Recalling his o’camp experience does not arouse strong feelings for Au, who treasured the development of independent thinking over group identity during his university years. He tries to jog his memory by looking at his old diary.

He remembers a part of the o’camp where freshmen had to go into the community to interview people like social workers, professors and politicians. After the interview, they gathered together for discussion and mainly talked about how a university student should contribute to society.

The activity chimes with the spirit of the times. In the 1980s, many people were worried about the return of Hong Kong to China. Students were among the first group of people who came out in support of the return of Hong Kong and oppose colonialism.

During Au’s time, the government was drafting the Basic Law. Students felt they should be contributing to the debate on social policy and politics.

Although Au was critical of the emphasis on collective thinking and the group impulse behind o’camp, he still thinks the team identity and spirit was weaker in his time than now.

Group leaders were just group leaders, they were never called Jo ma (group mum) and Jo ba (group dad) as they are now. It was a person’s individual choice whether or not to listen to their group leader. The authority of the group leaders was not so strong.

Neither was there any competition between departments or colleges. Au believes the battles in the recent o’camps which create a common enemy are a fast way to unite a group.

“Somehow o’camps can gather individuals and build collective consciousness, which can also be transferred to the next ‘generation’ of freshmen,” says Au.

At Hong Kong University in the 1980s, however, the emphasis was also on character-building.

Kirindi Chan Man-kuen was on the Organizing Committee of Swire Hall o’camp in 1982. She says the o’camps were meant to shock the freshmen out of any sense of complacency or preconceived notions of their superiority.

“You might be top in your secondary school. But when you come to a place where everyone is talented…you are made to feel the difference in a short time,” Chan says.

The freshmen were supposed to undergo “socialization” in the university and to this end they organized adventurous activities, such as hiking at night, taking down bus stop signs, sneaking into laboratories to get hold of a certain live specimens. The aim was to force them to step out of their comfort zone.

The difference in the pecking order between freshmen and senior students was also emphasized. Freshmen had to do what seniors required.

By the 1990s and noughties, o’camp activities had changed yet again and began to attract the attention of the news media. Chan, a senior executive at Radio Television Hong Kong, attributes some of these changes to influences from the media and the popularity of more provocative games among teenagers, “particularly in variety shows, such as [TVB’s] Supertrio Supreme, which embarrasses or degrades people for entertainment,” she says.

Pete Yeung Pak-yu who joined the Journalism and Communication School o’camp of CUHK in 1998 remembers being a “victim” in such games. Yeung says that as there were always more girls than boys in the school and the concept of “females are superior to males” was presented through games.

There were only 10 male students in Yeung’s year and he says o’camp student organizers set up some games to make the male freshmen lose. The 10 male freshmen were then punished by being asked to roll on the floor together. Although Yeung was angry, he did not say so at the time.

He also remembers scenes when students would have to shout slogans against those from other departments while praising their own. He says as there were more girls than boys in his school, slogans were not offensive.

But in other departments like Engineering, where there were more males, the slogans were more provocative. He recalls a song from the Engineering Department with lyrics about watching a woman being sexually assaulted.

While he was upset about having to roll on the floor, Yeung says that when he was on the o’camp organizing committee in 1999, he had the same mindset and liked to play tricks on freshmen. Committee members behaved that way because they were also treated like that when they were freshmen.

Apart from the introduction of games and activities that could embarrass or insult others, another development in o’camps in recent years is the growing power and prestige of group leaders in the camps.

Theron Sum Chun-yin was a chief group leader in the o’camp of Chung Chi College, CUHK in 2003. He says he felt great satisfaction when all the freshmen appreciated him and applauded him.

“Within few days, Jo ba (group father), Jo ma (group mother) become very close to their jo kids (groupmates)…the bonding, the unity between generations all starts from o’camps.”

“Being the group leader leading seventy or more freshmen in the o’camps, I felt a sense of responsibility as well as superiority,” continued Sum with a bashful face.

O’camps have changed down the years, but some things have remained constant. Meeting teachers, previewing the courses of the coming academic years, learning practical skills and absorbing information such as course enrolment strategies and games with different messages have always been a part of o’camp. Almost all students join o’camps and they are where most university friendships begin.

The central aim of o’camp has always been to prepare freshmen for university life, whatever that may be.