Citizens connect to the world through science

by Doris Yu

Twice a month, Masee Fung, his teammates and other volunteers ride their bicycles along narrow tracks the width of a hand span to reach the small farmland site they rent in Yuen Long’s Ching Tam Village. Then the citizen scientists turn on their flashlights and find their way through to the shrubs where, according to a year-long observation study, they will find the most fireflies.

As they turn off their flashlights, the insects glow brighter and they start counting the fireflies and recording their species based on the knowledge they gained in a two-hour training session.

In the two-hour training conducted by Fung’s team, city dwellers learn about the colour, size and flashing pattern of four kinds of fireflies. Even without a relevant degree, ordinary people can be transformed into citizen scientists who are capable of helping to gather data. “Even ordinary citizens, kids and primary students can [distinguish species] as long as they can see and distinguish colours,” Fung says.

“Citizen science” refers to scientific research conducted by enthusiastic amateurs. Data collection, in the form of recording all encounters with specific livings organisms, is the most common activity for Hong Kong’s citizen scientists.

Unlike large-scale citizen science projects, such as Green Power’s Butterfly Surveyor project and the Hong Kong Bird Watching Society’s Hong Kong Sparrow Census, Fung’s team prefers to keep their research project low-profile. Doing less promotion and holding fewer activities mean they have fewer volunteers and less funding and data. But it also means the team can avoid attracting people who join for the wrong reasons – such as photographers who want to shoot fireflies and people who are just looking for a quiet place for a picnic.

Fung is not concerned about how many volunteers he can get, what matters to him is whether they really appreciate nature and want to get involved in citizen science. His team’s main purpose is to learn about the habitat of fireflies and to create a firefly-friendly and biodiverse little corner in Hong Kong.

“Those who can really read our message will find us,” says Fung. “We do not have to sell it.” So far, this low-key approach has managed to attract two volunteers who are truly passionate about learning, enjoying and contributing to firefly biodiversity in Hong Kong.

Like Fung’s volunteers, Lau Yun-kwan, a third year environmental science student at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), finds that joining citizen science projects makes him more sensitive to natural surroundings.

Last summer, Lau volunteered to be one of Green Power’s 248 butterfly surveyors. Since 2008, the organisation has been recruiting and training citizen scientists to update its Hong Kong butterflies database.

After three months of lectures and field trips, Lau is more familiar with butterflies. He once spotted more than 30 Coliadinae butterflies, which may include very rare subspecies, on the CUHK campus. Much to his regret, they flew away in a few seconds, before he could verify them using his well-thumbed illustrated guide to Hong Kong butterflies.

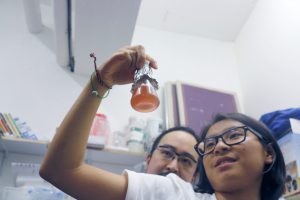

DIYbio Hong Kong, a newly-established “community of DIY biologists”, wants to do more than concentrate on any one family or species. The group wants to record Hong Kong’s biodiversity by “barcoding” all species in its Hong Kong DNA Barcode Project.

The project’s organisers, some of whom are trained biologists, are inviting the whole community, especially students, to collect and transport samples of plants, insects or animals they have discovered to DIYbio’s community lab. Members will teach citizens how to extract DNA and process it through a polymerase chain reaction machine to undergo sequencing. Each sequence will generate a unique barcode for each organism.

The group’s founder, South African biologist Gert Grobler, hopes to inspire people to engage with nature.

“We want to get people in touch with nature,” says Grobler. “People catch Pokémons, [lead] virtual lives; they don’t know about the real lives.”

Through the process of learning about molecular biology and extracting and analyzing DNA, Grobler hopes citizen scientists will be inspired and motivated to conserve the natural world.

Maria Li Lok-yee, the director and secretary of DIYbio says: “You need to take ownership of your environment, your surroundings, in order to love it and preserve it.”

However, the high cost of purchasing DNA-sequencing equipment makes it difficult to achieve the project’s goals.

Like many citizen science projects, DIYbio does not have sponsorship from big companies and institutions. Mike Yuen Chun-kwong, another core member of DIYbio and a retired science teacher, tries to keep research expenses down by either buying cheap copies of equipment components from the Chinese online retail platform Taobao, or seeking second-hand donations from local universities. Sometimes, the do-it-yourself biologists make plastic components using a 3D printer to build their own machines for experiments.

For his Hong Kong Moth Recording Project, Roger Kendrick chose an easier and cheaper method to promote moth preservation. He started a moth survey on iNaturalist, a global database available online and on mobile apps. Around 1,500 photographic records of moths in Hong Kong have been collected so far and Kendrick believes most were submitted via the app, which automatically stores the geodata of the photos.

Kendrick uses the internet to allow citizen scientists to store and share their data, which then becomes a reference point for other citizen scientists as well as experts. He thinks the feedback loop between experts and amateur scientists is crucial. This is why he constantly posts the observations and statistics of sightings to members of the moth-enthusiast community. He ranks users according to how many observations they make and species they spot as a way to encourage more collection, discussion and conservation.

Barcoding and recording though apps are among the new methods citizen scientists can use to conserve those species that are still around and can be barcoded and photographed. But, in fact, citizen scientists have been playing a part in conservation for years, including helping to protect critically threatened species in Hong Kong, by influencing public policy.

For Martin Williams, a writer specialising in conservation and the environment, “citizen science” can often be a fancy term that does not have much meaning in itself. What matters, says Williams is that people love nature. That love of nature may drive them to observe it, and when they find the nature they love is under threat – they will record as well as observe. They become citizen scientists.

He cites the actions of voluntary scientists who discovered the rare black-faced spoonbill in the Mai Po Nature Reserve. Williams’ friend Peter Kennerley, a British birdwatcher, discovered how endangered the spoonbills were in Hong Kong in the early 2000s. Like many citizen scientists, he initially recorded the number and distribution of the birds solely out of curiosity.

His observations eventually captured media attention in China, Vietnam, Japan and Taiwan and made the spoonbills famous. The Mai Po marshes, the habitat of spoonbills, are protected from development plans because of their ecological value.

Research by citizen scientists’ has also been used in attempts to thwart some development plans. Williams gives the Lung Mei Beach development plan as an example. In 2008, volunteers of the Hong Kong Wildlife Forum found 216 species in the inter-tidal range of Lung Mei Beach in Tai Po, 36 times the number identified by professionals hired by project consultants.

Williams thinks the marine-life conservationists worked harder to identify species because they are more concerned about marine biodiversity. He says government-hired professionals may have a conflict of interest. Citizen scientists are unpaid and their research is “not rooted from money”, says Williams.

Although the man-made beach project at Lung Mei was finally given the green light, Williams thinks Hong Kong Wildlife Forum’s intervention is a good example of passionate citizen scientists doing much more than just collecting data.

“It’s useless to write it down only by and for yourself,” says Williams. “If you tell the world about it, you could have valuable result.”

Edited by Natale Ching