Does society recognise associate degrees?

Reporters: Yannie Mak & Matthew Leung

Every year starting in late March, Hong Kong’s secondary schools become battlefields for tens of thousands of anxious students taking their A-level Examination. This year, they are joined by students taking the new Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination. This means there will be more than 110,000 students sitting their school-leaving exams this spring.

Many of them will hope to gain the grades needed to secure entrance to a University Grants Council (UGC) funded undergraduate programme. But only around 15,700 will make it due to the limited number of places. Most students are bound to consider alternative paths if they wish to pursue their studies.

The associate degree was introduced by the government in 2000 to boost the number of students in tertiary education. Various institutions providing associate degree programmes have since positioned themselves as stepping-stones to entering degree courses and over the years, their programmes have attracted a fair number of students.

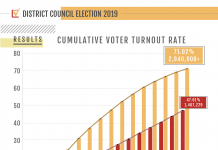

According to the Information Portal for Accredited Post-secondary Programmes (iPass), the number of enrollments to full-time associate degree programmes reached 27,500 in academic year 2010-11, seven times the number in 2000.

Yet the qualification seems to get a bad rap from society at large. With a certain amount of stigma attached to it and uncertainties about future prospects, deciding whether studying for an associate degree is a justified or risky move depends on individual expectations.

Kong Ka-sin, a first-year associate degree student in psychology at the College of International Education, chose the associate degree path as she thought it would give her a better chance of getting onto degree programmes than a vocational school would.

However, she thought twice before making the decision. “I held a negative view towards associate degrees when I was in Form Five,” says Kong. “Is it really corresponding to degree programmes? Is it really recognised [by employers]?”

She now realises the courses have helped her discover where her interests lie and encouraged her to strive for better career prospects. Kong believes this knowledge benefits students whether they eventually continue their studies in university or join the workplace.

After seeing the possibilities of further study from the experience of her seniors, Kong now feels more comfortable about her choice.

What concerns her now is how much her tuition costs. According to the Education Bureau (EDB), more than half of the local self-financed institutions providing associate degree programmes plan to raise their tuition in the coming academic year by five to 10 per cent on average.

Shirley Heung Shuk-yi, a second-year associate degree student in health studies at the Hong Kong Community College pays around $50,000 a year in tuition fees. She is unhappy about what she gets in return. Heung complains that most of the time a dozen students have to share one life-sized anatomical mannequin for practicals.

Heung attributes this phenomenon to a sharp increase in student intake. Heung says there were fewer than 100 students in her programme the year before she was admitted, but that number has now more than tripled.

According to figures from the EDB, only six per cent of the 30,000 students enrolled in associate degree programmes in 2011-12 will be able to further their studies on UGC-funded degree programmes. The rest may have to consider self-funded degree programmes offered by local universities, which charge $20,000 to $40,000 more per year than the UGC-funded degree programmes.

Rocky Tam Lok-kei, a second-year student in associate of social science programme at the Community College of City University, explains that graduates from self-funded degree programmes are usually welcomed by employers as they tend to have more practical knowledge and their courses are designed with industry needs in mind.

This makes self-funded programmes a good option for those who do not get onto UGC-funded degree programmes. But just as some doors open up for associate degree graduates, others close.

The City University of Hong Kong recently announced it would slash admissions for self-funded degree programmes from 652 this year to 90 in 2014-15. The university says the move is to ensure quality teaching. But Tam, who is a representative of The Group in Concern of the Cutting of Self Financing Top-up Degree Programmes of the City University, accuses the university of neglecting associate degree students’ expectations.

This development may just be the latest twist in the fluctuating fortunes of the associate degree in Hong Kong. Its reception has been mixed in the 12 years since it was introduced.

Fung Wai-wah, president of the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, says that because of rushed implementation, the associate degree faced four major problems in the early days.

First, a lack of resources from the government meant quality was varied across courses and institutions. Second, corresponding paths for further studies were not well planned. Third, there were no financial subsidies for teaching facilities, which led to expensive tuition fees. Fourth, the government’s failure to take the lead in recognising the qualification made job-seeking challenging.

Fung says that because the programmes were not government funded, there was also a lack of regulation on quality and standards. Institutes that manage to enroll a large and stable number of students may make huge profits without having to invest much of it on students, while other institutes struggle financially. Fung describes this as an unhealthy phenomenon.

Some of the problems are improving. For instance, the path for further studies has been widened thanks to an increase in the number of UGC-funded degree programmes especially for associate degree graduates. “But we are not satisfied yet as the ratio is still low,” Fung says.

Even if the number of such degree places were further increased, a large proportion of associate degree graduates would still have to enter the workforce rather than pursue further study.

In 2008, the Qualifications Framework system, a seven-level hierarchy, was introduced by the government. Associate degree lies in the fourth level together with higher diploma, in between diploma and bachelor degree.

But compared with the higher diploma, which has been around for half a century, the associate degree is not as well recognised by the government. There are 300 to 400 government positions which are open to graduates from higher diploma programmes, but fewer than 100 for associate degree graduates, according to Fung Wai-wah.

“We advocate the government to take the first step to increase the number of recognised positions, so as to give confidence to other employers [towards associate degree graduates],” says Fung, who also questions why the government refuses to disclose exactly how many associate degree graduates it hires every year.

Today, there are over 20 self-financed institutions providing associate degree programmes. Even students themselves do not know them all, so it is unsurprising that employers may be uncertain about the programmes.

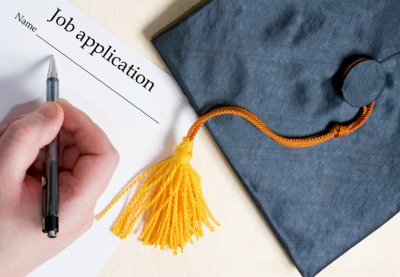

However, Paul Arkwright, publisher and editor-in-chief of HR Magazine, says employers are not that concerned about the type of degree a job-seeker has. Candidates do not get hired just because of an associate degree or a bachelor degree.

“In the work place, it has changed a lot. It has a lot less emphasis on the academic,” says Arkwright. “Practical working experience would be their [employers] number one concern.”

From his contact with human resources hiring managers, Arkwright says he knows most fresh graduates, including bachelor degree holders, are criticised for not having working experience.

Therefore, he suggests that associate degree students should at least fight for some working experience, even if it is unpaid. “There’s no excuse for getting no working experience,” Arkwright adds.

A businesswoman, who participated in a business forum organised by HR Magazine, says she recently accepted an application from an associate degree graduate because of his good English. She was less concerned about what type of qualification he had. She adds that with the increasing number of bachelor degree holders, all degree holders are worried about getting a job.

It appears that the associate degree does not offer a sure path to further studies or great career prospects. But that does not mean it serves no purpose at all.

In the eyes of Professor Chung Yue-ping, from the Department of Educational Administration and Policy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, providing more education opportunities is beneficial to society overall.

Chung describes pursuing more knowledge as an investment. Choosing to continue studying after graduation from secondary school instead of working could mean losing a few years of money-earning opportunities yet, “it is about enrichment of knowledge and enhancement of abilities, which are useful for a person throughout his life.”

Chung suggests associate degrees could be improved if the government allocates more resources, including money and land. He says the quality could be improved too by ensuring a satisfactory level of teaching staff qualifications and course content.

In recent years, some have expressed concern over what they call the “overflow” of sub-degrees. They argue that the increased number of students in higher education dilutes quality and standards.

But Chung regards “overflow” as the indiscriminate distribution of qualifications by institutions rather than an increase in the number of students.

As long as the quality of associate degree programmes is ensured, providing more higher education opportunities is the “foundation of a society’s civilisation,” says Chung. “It [education] is an investment in yourself, an enrichment of knowledge, an increase of ability, which benefits your entire life.”