Stakes are high as young gamblers find it hard to quit

By Donna Shiu & Edith Lin

It is a refrain that will sound familiar to anyone who has had a problem with gambling. “When you lose HK$1,000, you want to get that HK$1,000 back; when you win HK$1,000 easily, you want to win HK$1,000 more,” says James (not his real name), a 22-year-old university student.

James started gambling six years ago when he was 16. He asked an adult friend to place a bet on a football match on his behalf. He accumulated losses of HK$2,000 over six months. It was an amount he felt he could absorb, so he continued to gamble despite the losses. In fact he thinks an “appropriate” amount of gambling is not harmful to individuals or to society as long as gamblers can control their mindset. “Gambling is an innate mentality of human beings,” James says.

It seems that gambling habits can begin early – according to findings released by the Sociology Department of the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2010, 28 per cent of secondary school students had gambled for money in the 12 months prior to the survey. Card games and mahjong are highly popular among students.

Raymond Wu Man-wai, supervisor of the Hong Kong Gamblers Recovery Centre acknowledges gambling can be a problem for teenagers under 18. But Wu says gambling addictions usually develop and worsen once youngsters enter adulthood.

Wu says teenagers usually learn how to gamble through watching their family members playing mahjong or purchasing Mark Six lottery tickets. “Before age 18, [the idea that] “gambling is not a big deal” is cultivated in their mind. Their parents gamble. Their society accepts gambling, which means the Jockey Club allows gamblers to place their bets after they are 18,” says Wu.

Once youngsters become adults, they can earn money through full-time and part-time jobs and borrow money on their credit cards. It is with this new-found capital that their gambling behaviour may begin to spin out of control.

Indeed, Wu says fewer than 5 per cent of the centre’s clients are under the age of 18. But when teenagers do gamble, it is difficult for their parents to spot the problem. “Gambling is colourless and tasteless,” Wu says. Teenagers can easily find gambling games online or available for download as mobile apps. The games usually start off free, but they soon require players to buy points or tools via credit cards or other kinds of payment if they want to proceed to a higher level.

One of Wu’s clients, a secondary student, was obsessed with the Texas hold’em mobile app and had a very high rank in it. To unlock higher levels, the student stole his siblings’ credit cards and even classmates’ mobile phones for resale in order to pay for his habit.

Wu says students may hide in their rooms and bet through mobile apps, with parents oblivious to what is going on until they receive bills from the bank or loan companies. They usually try to settle the debts run up by their children without seeking help from social workers.

However, the youths will continue to gamble, “Step by step,” says Wu. “They do not become addicted all of a sudden,” he adds.

“You neither treat the money you have won nor the chips you are holding as money. You don’t treat it as your hard-earned money,” says 20-year-old Thomas, who does not want to disclose his real name. After being admitted to university, Thomas tried his hand at all kinds of investments, such as buying stocks, warrants and futures, for the purpose of saving up to the make the down payment on a flat.

Thomas was once a full-time investor, skipping classes and staring at the stock market numbers around the clock. In the end, he lost more than HK$50,000 in a single month on futures. This wiped out all the savings he had made by working three part-time jobs. At that moment, he thought there was no hope in life.

But then he switched to gambling in Macau’s casinos. He was greatly excited by the quick changes in fortune he experienced when playing table games. The teenager astonished other gamblers by placing three separate bets, ranging from HK$4,000 to HK$7,000 on table games when he had only HK$20,000 left.

Thomas recalls one occasion when he lost HK$10,000 in one bet on the table. He was left utterly shocked, could hardly breathe and felt his legs were shaking. He thought about how he could not afford to lose all he had earned in the past two months in just one second. He was so angry that he overdrew his credit card to gamble again. On another occasion, he also tried to borrow over HK$10,000 from his girlfriend, claiming it was financial support for his daily expenses.

Thomas says he is frugal in his daily spending because he wants to save money to play table games. He has no doubts about which he would opt for given a choice between a HK$20 lunch set or a HK$50 one. “Why not save HK$30 for gambling? Choose between HK$3,000 and HK$2,000 for table games? HK$3,000 for sure,” he says.

The way he sees it, he can never make enough for a down payment on a flat by working part-time in an office for an hourly wage of HK$50 or by giving private tuition classes for children at HK$150 per hour. The only way he can make a few hundred thousand dollars quickly is through gambling.

He has spent so much time studying the theories behind winning strategies for card games like Texas hold’em and Blackjack that his grades nosedived and he no longer receives a scholarship from his university.

Despite the drawbacks, he says gambling is part of his life. He reckons it is impossible to quit and that an “appropriate” degree of gambling is an acceptable form of entertainment. He says gambling is a necessary outlet for everyone to relieve their stress.

Yet he denies that he has a problem or that he is a pathological gambler because he thinks he could stop himself if he wanted to. Thomas explains it is normal to lose money in luxurious casinos – including when he lost all his savings of HK$80,000 over four months this past summer.

However, according to Jessie Wong Yuk-ming, a social worker and the centre-in-charge of Yuk Lai Hin Counseling Centre, Thomas would probably be assessed as a problem gambler according to DSM IV. DSM IV is a psychological assessment tool designed by the American Psychiatric Association. Ten symptoms are given as indicators in the assessment for problem gambling. They include always being preoccupied with gambling, chasing losses, increasing the amount of money spent on gambling, getting restless when trying to quit gambling, and using others’ money to continue gambling. People are assessed as problem gamblers if three or more symptoms are indicated, and as pathological gamblers when five or more symptoms are present.

Wong says Thomas has at least three symptoms indicated in DSM IV, as he tried to chase his losses, is preoccupied with thinking of ways to get money through gambling and tried to borrow on his credit card and from his girlfriend. She says problem gamblers have a psychological dependency on gambling and harbour irrational thoughts that gambling can help them to make money.

Wong adds teenagers are susceptible to pressure from their companions, especially when they have tense relationships with their families. They believe that gambling is a way to maintain status in their relationships with friends and this gradually leads to addiction.

“He can lead others to gamble, show off his ‘vision. [When he wins] he can treat people to food, it gives him a feeling of superiority,” says Wong. Introverted and arrogant youngsters are particularly prone to developing gambling addictions since they are trying to establish a self-image.

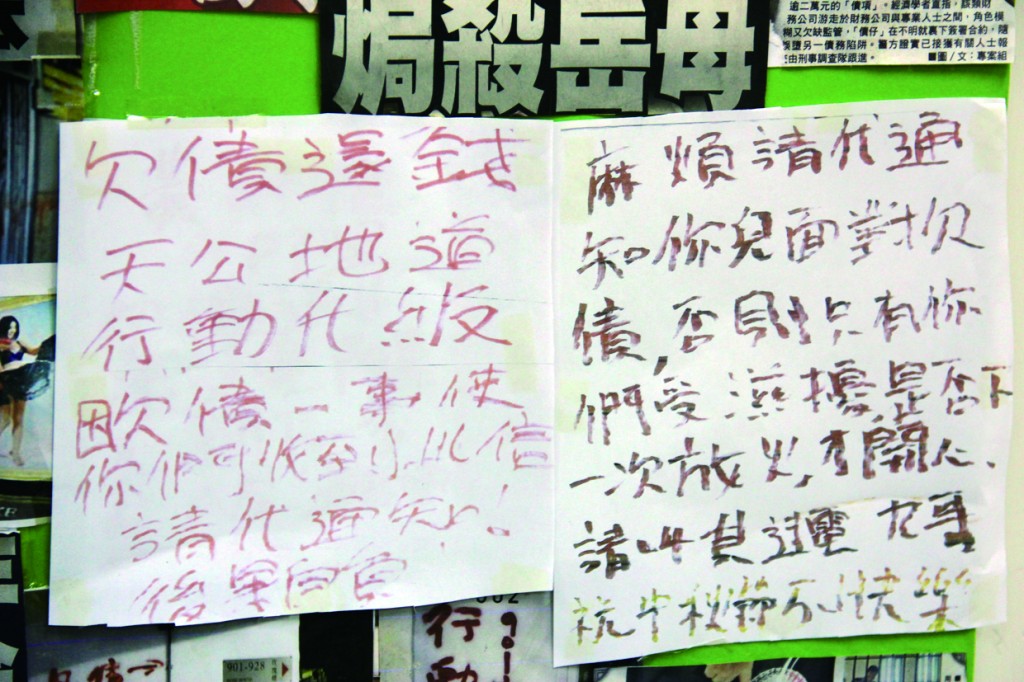

Gambling can also lead to crime as gamblers resort to illegal methods to raise money for their games. One of Wong’s cases, Alex (not his real name) began betting on football matches in secondary school as a result of peer pressure. He acted as a banker in school and failed to pay his punters. After disclosing the incident, he was kicked out of school and stole bicycles. Alex was referred to Wong by a probation officer after being charged with theft.

To quit their gambling addictions, Wong thinks gamblers need to first see and admit their gambling is a problem. They should also take action to stop their gambling habits, such as cutting off their betting accounts. Wong says they have various support groups and activities, like a volunteering group and a football group, to re-establish their clients’ social circles and help them adopt a more positive lifestyle. Each support group comprises 20 to 30 people, including clients’ family members.

Like Wu’s centre, Wong receives about 200 cases a year and less than 5 per cent involve people aged below 25. Teenagers and their families seldom seek help until the problem gets out of hand. Wong cites the example of a client she refers to as Travis, whose mother sought help for her son to quit gambling. Before coming to Wong, the mother had already paid off debts of tens of thousands of dollars for Travisthe son. She decided to seek help from the recovery centre after Travis her son borrowed money again, just three months after she had paid off the previous debts.

Wong urges family members of young gamblers to seek help, get counselling and to join cell groups in family counselling centres. “To successfully quit gambling means the person has changed their attitude, has changed their values,” Wong says. Normally gamblers who stop betting for six consecutive months are considered to have successfully quit. Social workers also examine their associated problems, such as insomnia, work performance and interpersonal relationships.

Wong says the government has not provided sufficient resources to support recovery services. She says Yuk Lai Hin Counseling Centre relies on the Ping Wo Fund, a fund supporting gambling recovery services which, ironically, is funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club. However, she says she has no idea whether the scheme will continue to allocate funds to the centre after the end of the current contract. “The government has made no promises or plans to allocate a part of its financial budget to subsidise gambling recovery services,” Wong says.

Despite uncertainty over its long-term future, Wong’s centre is far better resourced and funded than Raymond Wu’s Hong Kong Gambling Recovery Centre, which relies on public donations. Wu agrees the government could do a better job at curbing gambling. He notices students learn about the downside of drug use from their textbooks beginning in primary school or even kindergarten. But you will not find any in-depth discussion on the harm of gambling in students’ textbooks. “The government can only tell you not to be addicted to gambling…But you can’t say “Not now, not ever” for gambling,” Wu says.

Edited by Cherry Wong