Reporters: Andrew Choi Tsz-hong and Piano Ho

On a typical work day, 50-year old Tsoi Wai-man wakes up at around 5 a.m., gets ready and walks to the office to start his shift as a security guard at 6.45 a.m.

The shift is supposed to end at 7 p.m. but he often ends up staying longer, without overtime pay. Then, he goes home for a quick dinner and shower before it is time for bed and a night’s rest before another long day of work starts again.

“I don’t even have time to watch television. I never have my own time. I feel like I have sold myself to my boss!” he says.

His reward for selling himself to the boss is a monthly salary of $7,495 for a 12 hours a day, 26 days a month job. However, his income is unstable because he only gets to work whenever his company calls him to take up a temporary vacancy. “You work to death when you get calls. But you may get crazy waiting for the company to call you to work after a few days.”

Tsoi’s story is a common one for Hong Kong’s working poor. They tend to be people in their 40s, working 10 or more hours a day and for wages as low as $25 an hour.

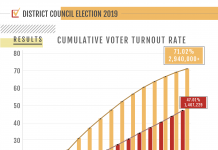

A report released by the charity Oxfam earlier this year showed that between 2005 and the second quarter of this year, the number of working poor households had increased by 12 per cent to 192,500. This means one in every 10 families where at least one member is working has a monthly income that is less than half the median income of families of a similar size.

Like many of the working poor, Tsoi has a basic education level. He dropped out from school after form two and has been working for 35 years. He has been working as a security guard since 2005. It is a tough job – Tsoi summarized it using three descriptions – long working hours, low salary and harsh working conditions.

He once worked for nearly 15 hours but was only paid $307. Also, he once worked just 18 days in two months. He is barely able to maintain his daily life with the meagre and unstable income. “Sometimes, I have only one meal a day,” he says.

Security companies may require Tsoi to work anywhere in Hong Kong and he has to spend time and money on travelling to different places of work.

Tsoi is disillusioned with the security industry and has tried searching for different jobs, such as logistics clerk and outdoor office assistant. His attempts have all failed as employers prefer to hire younger, better educated workers who are willing to accept a low salary.

He also believes he has been punished for exercising his rights. Tsoi appeared in the news media when he demonstrated for better workers’ welfare. Afterwards, his then employer told him to leave, just a week before his probation period ended. “I am sure they fired me because of my actions outside the Legislative Council,” Tsoi grumbled.

But Tsoi’s worst employer was the one he had around two and a half years ago. At the time,his father, a long-term patient, was taken into intensive care. He asked for leave from work but his boss rejected his request. Tsoi had no choice but to quit his job and rush to the hospital. He was there when his father passed away.Still, Tsoi did not have enough money to buy a coffin and hold a funeral for his father. So he asked his friends and the Social Welfare Department for help.

He describes that period as the hardest and darkest time he has ever experienced. His message to employers is: “Labour is your asset, not your burden.”

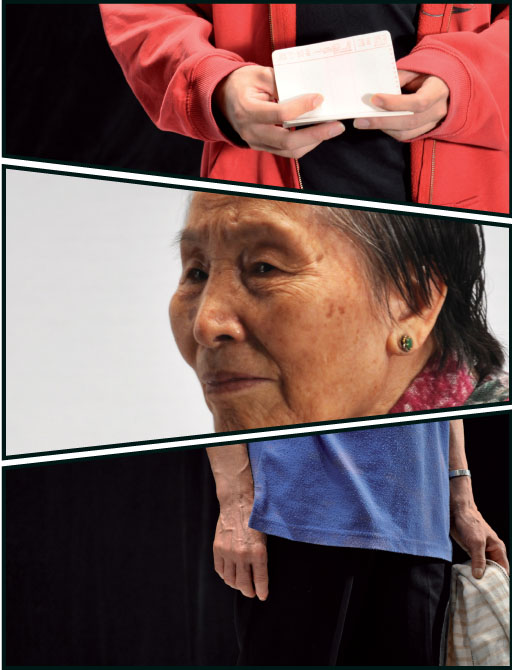

According to an earlier Oxfam report, most of the working poor are employed in lowskilled service jobs. Many are middleaged women who face both age and sex discrimination in the workplace.

Kan (not her real name), who is nearly 40, is one of them. The mother of two works two cleaning jobs, 15 hours a day. That leaves her with nine hours to eat, sleep, do household chores and spend time with her children. She earns $8,400 a month and together with her husband, who is also a cleaner, the family has a total income of about $15,000.

The family of four lives in a tiny metal rooftop shack and one third of the couple’s earnings is used to pay the rent and utilities bills. “We have to be extremely frugal in order to support our expenses and we have no savings at all,” Kan says.

Since they arrived in Hong Kong from the mainland in 1996, Kan’s family has never dined out or had dim sum during holidays or festivals. She spends around $70 to $80 per day to cook two meals for four people, equivalent to $10 per person each meal.

She has not applied for Comprehensive Social Security Assistance because she believes in self-sufficiency. “I am afraid people will think I am greedy if I ask for too much help from the government.” The only assistance she gets from the government is money for internet access and textbooks for her sons.

And it is to her children that Kan looks for hope. “I always tell my sons to save as much as they can, and to study harder in order to have a better future,” she says. “I hope they can go to university and are able to pay for their tuition fees.”

“No matter how poor we are, it is important that we are still together,” Kan adds, “we are poor, but we are joyful.”

However, she does also hope that the government and society can do something to help the lot of the working poor. Kan earns as little as $20 an hour and outsourcing is the main reason for her low wages because subcontractors at each level take a cut of the money for the work. She believes the government tendering system contributes to the problem of the working poor. Companies that make the lowest bids win the contracts and squeezing workers’ wages is the obvious and easy way to keep costs down.

“I hope that labour will not be exploited so seriously,” Kan says.

Mr Wong, the sole breadwinner of a six-person family also hopes the government can do more. Since migrating to Hong Kong from the mainland in 1996, Wong has worked in a carwash, a hotel and in a restaurant. He currently works as a cook on the night shift – from 6 p.m. to 4 a.m. – in a Mong Kok restaurant, for $12,600 a month.

The only time Wong spends with his children is in the mornings after work. “Even though I am sleepy, I will take my son to kindergarten in the morning,” Wong says. Other than that, he only has four days off each month. His job has taken up most of his life, but he is stoical. “A fair exchange is no robbery,” he sighs.

With his wife, sister, grandmother, a child at kindergarten and a newborn baby to support, Wong has to find ways to cut expenditure. For instance, he takes bread home if any is leftover at the restaurant and he has sought food assistance from the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The service provides rations of rice, noodles, tinned food and baby formula for up to six weeks.

He also walks for an hour back from Mong Kok to his home in Lai Chi Kok when he finishes work every day. This saves him the $7.40 bus fare.

Most of Wong’s income goes on rent and food. He spends around $3,000 on rent for the family’s public rental flat. He also needs to satisfy the needs of his growing children, so he hopes his wife will be able to find some part-time jobs when she no longer has to look after the children full-time.

In terms of government assistance, Wong thinks the waiving of the rent for public housing for three months this year was the greatest help for his family.

Nelson Chow Wing-sun, a chair professor at the Department of Social Work and Social Administration at TheUniversity of Hong Kong, says the freeze on public housing rents since 1997 has helped the poor to get by. But he believes the government should keep prices low and stable for daily goods so people at the grassroots level will be able to maintain their basic living even if they do not earn much.

Chow points out that the rising rent for small shops in public housing estates, under the management of The Link REIT has hit the poor hard. These shops have had to raise prices to cover their costs but the poor have not had pay rises to match. “If a family of three to four just earns about $6,000 to $7,000 a month, they will have to think twice before spending every dollar,” Chow says.

Chow describes the problem of the working poor as a problem of excessive supply and decreasing demand. He says there has been a decrease in demand for lower-skilled workers since the 1980s, when Hong Kong factories started to move to the mainland.

This was coupled with an increase in migrants from the mainland.The number of new arrivals from the mainland swelled from the mid-1990s, when more relaxed arrangements for entry to Hong Kong brought many older and poorly educated migrants from the mainland. These workers had little choice but to take on low-skilled jobs, for instance as security guards, cleaners and waiters.

Another crucial reason for the large numbers of working poor is that there was no compulsory education in Hong Kong until 1978. Therefore, many middle-aged workers are likely to have a low level of education and can only do manual work now.

However, Chow is optimistic about the future because he believes better education will provide more opportunities. The literacy rate is high in Hong Kong and, overall, schools provide a better education than they did in the past.

Chow believes this, plus the Employees Retraining Board, which offers vocational rehabilitation for unskilled workers, will lead to an improvement in the quality of the workforce. “If employers want to hire them, they need to pay better salaries,” says Chow.

Chow supports the implementation of a minimum wage and says around 300,000 workers will benefit from the new $28 an hour requirement. However, he concedes this is not a silver bullet for solving the problem of the working poor. It is structural, he says, and so deeply entrenched that only over time will the government and society find an answer.

Thanks for spotlighting Hong Kong’s working poor in this article. The woman who pushed trash in your photo reminds me how certain things in HK have not changed since I was a kid, when trash was manually and tediously moved the same way. The crux of the problem of poverty is, in my view, caused by inequitable distribution of wealth within society. Hong Kong’s income and capital gains tax rates are among the lowest in the world, which benefit local and foreign earners and investors alike. Taxes are consistently low due to consistently available source of cheap labor to ‘subsize’ those low tax rates. Sadly, the benefits of those low tax rates have never ‘trickled down’ society to lift people from poverty and to improve public education. As a result, the poor is trapped in a continuous cycle of poverty. All in all, I think HK’s mode of capitalism (based on exploitation of cheap labor) is hopelessly out-of-date.