Paying only $150 to enjoy a night full of jokes in Soho, Central

Reporter: Dorothy Goh

Tucked away between restaurants and bars in Elgin Street, Soho, there is a small basement club that only opens for business at night. About an hour before the club opens, people are already waiting at the entrance and hoping to get the best seats. They are not there for the drinks, the food, the music or even the conversation. They are there for laughs.

To enter the club, you have to walk down a steep flight of stairs. At the bottom is a cosy space where rows of chairs are neatly arranged, circling a simple stage with a microphone stand. This is where the magic happens.

The TakeOut Comedy Club (TOC), which opened in February 2007, is the first full-time comedy club in Asia. The club was founded and is managed by Jameson (also known as “Jami”) Gong, a 42-year-old Chinese American whose parents are from Hong Kong.

Gong says he has loved telling jokes and making others laugh since he was young. “It is my destiny, my calling,” he exclaims, looking upwards with arms opened wide. He grew up watching American comedian Johnny Carson on “The Tonight Show” and was amazed at how Carson could make him and millions of others laugh just by talking about everyday topics. The show inspired Gong to become a comedian.

Gong says he has loved telling jokes and making others laugh since he was young. “It is my destiny, my calling,” he exclaims, looking upwards with arms opened wide. He grew up watching American comedian Johnny Carson on “The Tonight Show” and was amazed at how Carson could make him and millions of others laugh just by talking about everyday topics. The show inspired Gong to become a comedian.

After quitting a career in retail management to pursue his passion for comedy, Gong worked as a stand-up comedian based in New York. He came to Hong Kong in 2006 with a mission to create a local comedy scene.

The TakeOut Comedy Club showcases both English and Chinese stand-up comedy but the style is closer to American stand-up than the performances of homegrown artistes like Dayo Wong Tze-wah. Here, the comics share an intimate space with a small audience, rather than play to large theatres. The shows also feature more audience interaction, with each comedian having less than 10 minutes to perform on stage.

According to Gong, comedy clubs are popular because they help to relieve stress. “Laughing helps improve blood circulation too,” he says.

Gong hopes to bring more laughter into Hong Kong people’s lives and thinks the best way to do that is to introduce stand-up comedy to the locals. “The expatriates already know what stand-up comedy is. They know they have to laugh out loud,” Gong explains. Before each Chinese show begins, Gong never fails to encourage the audience to laugh out loud instead of hiding their laughter. “We want Hong Kong people to realise the power of laughter.”

Nonetheless, he understands that in Chinese “culture” laughing in public is regarded as something to be embarrassed about. Pointing to a corner of the room, he says, “We had one show last week with a couple sitting over there. The girl was laughing so hard “hahahahaha” but her boyfriend was like “shhhhh” (Gong puts his finger to his lips) during the show. We saw it. We want to get people to see that it’s okay to laugh out loud.”

Although Gong wants to get the locals laughing out loud on a regular basis, TOC only showcases Chinese stand-ups once a month. “We don’t have big enough audiences or comedians to do that more than once a month, not yet,” Gong explains.

Live comedy shows are still quite new in Hong Kong but Gong is confident about the outlook for the business. “We’re hitting an untapped market and we have untapped materials that we can talk about on stage where you can relate with us. With a large market of seven million Chinese people, we hope to have Chinese shows every day. We hope to open up comedy clubs in Mongkok, Kowloon. Why not?”

Apart from his comedy shows, Gong gets invited to perform at schools and private events. “Now companies hire us for special shows, their parties as well. So, from the business standpoint, you can make money by being funny,” he says.

Gong has a positive mindset, even when it comes to disappointments and failures. “You will fail, but you will fail to succeed,” he says and strongly advises people to “just do it”.

This is exactly what Vivek Mahbubani did when he saw that TOC was organising a stand-up comedy competition three years ago.

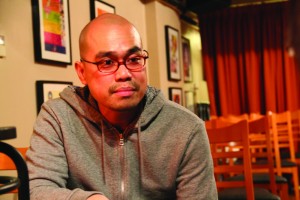

Mahbubani, a 29-year-old Hong Kong-born Indian, grew up here and speaks fluent English and Cantonese. He has admired stand-up comedians since he was a kid. “I remember sometime during university, I was watching stand-up comedy and decided that one day before I die I’m going to try it one time!” He won TOC’s first Chinese stand-up comedy competition in 2007, and was crowned the funniest Chinese comedian in Hong Kong that year and the funniest English comedian the following year.

Mahbubani is a website designer by day and a stand-up comedian at night. He even designed the homepage of the TakeOut Comedy website. Although he is squeezed for time between work and comedy, he is not willing to sacrifice either one.

Comparing English and Chinese shows, Mahbubani thinks the mentality of the audiences are very different. “A lot of the time in Chinese shows, people are like ‘Alright, let’s see how funny you really are.’ People are very critical in Chinese,” he says. However, after nearly three years of performing, Mahbubani realises that as long as the content is funny, it does not matter what language you perform in.

Mahbubani says stand-up comedy is a hobby that he “pursues professionally, but gets paid amateurly”. He spends at least an hour on writing every day. He values originality and works hard on his personal style. “It should be certain that when you write or present something, they would know that that’s his style. You can tell,” he says.,

As a Hong Kong Indian, Mahbubani jokes about his own ethnicity, but not to the extent that he is racist or intentionally hurts anybody. Instead of feeling bitter or angry in response to insults hurled by others, he channels them into his comedy.

“People call me ‘gweilo’, and I was upset because c’mon man, I’m not a gweilo. I’m an ‘ah cha’ which is the right term for my people. Do it correctly!” Mahbubani says that if you want to be racist, be the right kind of racist.

He is modest when asked how he feels about his growing fanbase, “I’m flattered,” he says. “I always joke that people are always telling me that ‘one day you’re going to be famous, the paparazzi are going to follow you’ and I’m like ‘this is going to be pathetic!’”

“I’ll never manage to get onto the front cover. It’ll be like ‘oh, he makes another website. Yay, it’s green colour this time. Look at him, he’s in the library, reading books, yay.’”

Mahbubani says his on-stage persona is a “very exaggerated form” of himself, offstage he enjoys private time alone. But every Thursday, he meets up with other, mostly local comedians at a cafe to try out new ideas and material. “We present it like we’re presenting to an audience but because it’s on a small table, intimate and everything, you get feedback immediately.”

Like Gong and Mahbubani, Matina Leung is a comic who performs routines in both English and Chinese. However, unlike them, she has not considered a career as a stand-up comedian. “It’s not a very popular form of performing art at this point in Hong Kong. We don’t have that big a market to support it,” she explains.

Like Gong and Mahbubani, Matina Leung is a comic who performs routines in both English and Chinese. However, unlike them, she has not considered a career as a stand-up comedian. “It’s not a very popular form of performing art at this point in Hong Kong. We don’t have that big a market to support it,” she explains.

Although Leung went to college in the United States, she never entered a comedy club until she returned to Hong Kong and was drawn by an advertisement for a free stand-up comedy workshop organised by TOC.

Having done stand-up for two years now, Leung has grown “more and more in love” with the format. Still, sometimes she finds it difficult to win over the audience with her jokes because she is female. “Chinese people are more conservative, they think that girls should be quiet, elegant, more reserved, and not funny.”

Being a woman does give Leung certain advantages though. She talks about the woes of being an unmarried Hong Kong woman in her 30s, and of how she used to date “cheap” men. “I can connect to female audiences better in general,” she says.

Despite being the “clown” among her girl friends, Leung still gets very nervous when she is on stage. Through stand-up comedy, she has a better understanding of her shortcomings and has built up her self-confidence.

Apart from her self-confidence and personal development, Leung has learnt to be professional and not let her emotions affect her performance. She remembers she once had an argument before a show. “I could not stop thinking about the fight. I went up on the stage and did a horrible job. I told myself afterwards that I’m never going to let that affect my performance again.”

Leung sees it as her job to make people happy, to make people laugh. She recalls that when the hostage tragedy occurred in Manila last year, everyone was very sad. “But the show must go on. The audience may feel sad too, but they just want to take a break and laugh for an hour.”

Gong, Mahbubani and Leung are all optimistic about the future of stand-up comedy in Hong Kong. “We’re creating a market from scratch. The possibilities are endless,” says Gong. After all, making people laugh is the “toughest but greatest job in the world.”