Yeung Sau-churk’s long journey from bored bookkeeper to rebellious artist to wise teacher

By Kristy Tong

In a local secondary school, a man wearing round, black-rimmed glasses and his snow-white hair in a ponytail steps into the art room. He greets each of the students like an old friend and asks whether they missed him. Throughout the lesson, he constantly asks questions and requires them take photographs to capture different visual elements of objects such as metal surfaces, lines, and corners, in order to train their observation and artistic sense.

Artist and teacher Ricky Yeung Sau-churk describes himself as “being possessed by other spirits” once he enters a classroom. The 64-year-old cannot wait to share his experience and knowledge. He enjoys teaching so much that even retirement cannot stop him and he is currently an artist-in-residence who teaches art workshops at various primary and secondary schools.

It is hard to imagine that Yeung spent the first part of his working life with his head buried in ledgers and accounts for 18 years. After completing secondary school at the Morrison Hill Technical Institute, Yeung followed social expectations and opted for a stable office job. But after spending five years doing accounting work for an audit firm, Yeung discovered he had no interest in figures and could not bear the working environment.

“I felt like I was in jail. There was no human touch,” Yeung says. Inspired by works such as existential psychologist Rollo May’s Man’s Search for Himself, he reconsidered his career path and decided to take action to create meaning in his life.

He remembered that he used to enjoy art lessons at primary school and his work was always chosen for display. To explore his potential, he started to take art classes after work at a Caritas Social Centre. Later, he switched to a three-year part-time course organised by the Department of Extra-Mural Studies of the University of Hong Kong (HKU) when he was 26. This was a turning point.

“My desire to create was so strong that I was like burning myself out,” Yeung recalls of that time.

The conditions for practising art were less than ideal. Yeung lived in a cramped tenement house with his family and had to wait for them to sleep before he could practise calligraphy on weekday nights. On the weekends he would just stay on the verandah to draw and paint. His family disdained his passion for art and told him he would end up begging if that was all he did.

Yeung did not have the courage to quit his job because he had to support his parents and save money to rent a studio. “There were two of me at that time. I sold my body in the day to earn money and redeemed it at night to do what I loved,” he says. “Through art, I found a release from the suppression of work and healed myself.”

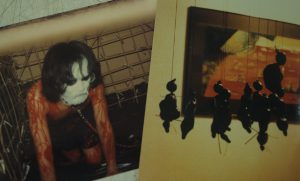

Yeung’s early artworks were radical, sexual, and vulgar. He was the first artist to adopt condoms as a material, using condoms, bamboo sticks and cotton wool to make the sculpture People vs People in 1981.The work depicts office workers’ attempts to cheat and outwit their colleagues. Another acclaimed work was his 1987 performance installation Man and Cage. In this installation, the artist was trapped in a bamboo cage, with his face painted white and his body painted red. He kept climbing inside the cage and yelling for 48 hours as a commentary on Hong Kong’s limited living space.

Yeung’s style during this period made some people uncomfortable. In 1984, two of his pieces depicting sexual intercourse were removed from an exhibition in the Ninety Seven Restaurant in Lan Kwai Fong after just one day due to diners’ complaints.

Although art provided Yeung with an outlet to vent his frustrations and disillusionment with work, society and his loss of his earlier Christian beliefs, it did not prevent him from experiencing a serious breakdown at the age of 37. The last straw was when he wrote eight cheques incorrectly in one day, something he had never done before. With his girlfriend’s encouragement, he finally quit his job and travelled around Europe for 15 months.

When Yeung came back to Hong Kong, he decided to pick up his studies and applied to study fine arts at HKU. His interviewers recognised him as a rising artist with some fame, and told him they were impressed by his performance in Man and Cage. He was accepted to study fine arts and comparative literature at the age of 39. Yeung threw himself into his studies to make up for lost time and spent most of his time in the library reading books.

Studying at university helped Yeung to find his path and put his life on the right track. He still had anger but wanted to transform it into energy for teaching, so he decided to apply for a teaching job after graduation. But it was not easy for a 42 year-old with no teaching experience. It took him a year to find a post as an art teacher in Fanling Lutheran Secondary School.

Yeung wore his hair long and treated his students like friends, which he says made him stand out as a “black sheep” in the Christian school. Being unmarried and without children, he could spend every day with his students and sometimes visited their homes to understand their family situation. When he met them outside of school on weekends, he did not stop them from smoking or swearing. His non-judgemental attitude won him the students’ trust. “They were close to me, and when they are close to me, that is when education starts,” he says.

Rather than becoming artists, Yeung hoped to educate his students to be citizens who care about society. “I want to teach more [students to be] Joshua Wong Chi-fung,” he says.

Therefore, Yeung combined the teaching of art with engagement in society. He introduced artworks related to social issues and encouraged his students to try incorporating social elements in their work. Under his influence, his students became concerned about society and expressed their feelings on particular issues through art. For instance, one student satirised national education as brainwashing students by turning his bedroom into an installation, which included a national flag blanket, Mao Zedong’s portrait, and Cultural Revolution slogans and posters.

Yeung did not just talk about politics in the classroom, he also took his students to observe social movements. In 2010, he took 18 students to the protests outside the Legislative Council against the Guangzhou-Hong Kong high-speed project. He was moved to tears when six of them volunteered to take part in a barefoot protest walk, prostrating themselves every few steps to express their opinions in a peaceful and humble way.

Beyond social movements, Yeung has also worked with the Arts with the Disabled Association Hong Kong for a decade and led his students to take part in community art with people with disabilities twice a year.

He once assigned his students to teach people with cerebral palsy, step by step, how to tie ribbons on the handrails of stairs. A simple action that would take the students just seconds, took those with cerebral palsy three minutes to complete. The experience surprised but also touched them. One was inspired to become a social worker, while others continued to do voluntary work at other community centres.

Yeung believes art is very powerful and can change people’s perceptions. He recalls that when he walked past a special school in 2001, he overheard a mother telling her daughter that if she did not study hard, she would be put in that school. Feeling bad about this, Yeung invited the school to join a community art project sponsored by the Hong Kong Institute of Education (now the University of Education). He assisted students with mild mental disabilities and their teachers to paint using different methods.

After three months, all the works were displayed at the main entrance of the school. The school’s neighbours reacted in a positive way and the project helped to change the school’s image.

“People classify [people with disabilities’] abilities as being high or low. We shouldn’t classify it that way. Their abilities are merely different,” Yeung says. Instead of seeing himself as teaching students with mild mental disabilities, he says they have actually taught him to understand their committed attitude and ability to concentrate.

Yeung says the students can understand what to do if he explains it to them clearly and slowly. What is more, they have their own creativity and painting styles. He admires their ability to express their feelings through their paintings without any burdens and says he could never imitate them.

Despite retiring in 2013, Yeung still contributes to community art. Last year, he helped to curate the first graduation show of “I-dArt”, a three-year art education course for the disabled and the elderly. He volunteered to teach six lessons and observed a student with autism who always ignored his instructions. The student would just write down the names of TV programmes, celebrities, and products in every lesson. To force her to try new techniques, Yeung took away her brush and gave her rolls of tape to make the words in a different way. The student was not used to this method at first, but she smiled when she saw the finished product and was willing to try the method again next time. The satisfaction from such encounters gives Yeung an incentive to keep teaching.

From downtrodden salaryman to angry young artist to wise teacher, Yeung looks back on his life with no regrets. “I lived in hell in the first half of my life and live in heaven in the rest of my life,” he says. “Life is full of twists and turns. If I did not have those experiences, I would not know how to teach my students now.”

Edited by Venice Lai