Once a thriving alternative to day schools, evening schools now struggle to survive

By Chloe Kwan, Venice Lai

When the sun sets and workers pack into buses and trains for the journey home after a long day at work, students at evening schools hunker down for their classes. They come from diverse backgrounds – some have day jobs and some are fresh out of conventional schools.

Although they have been in decline since the 1990s, evening schools were very popular up until the 1980s. In the 1950s, the arrival of large numbers of young refugees from the Chinese Civil War overloaded Hong Kong’s education system. The government and some non-profit-making organisations set up evening schools to satisfy the demand for schooling in the absence of free universal education.

There were two main kinds of evening schools. The first taught the conventional secondary school curriculum, while the others aimed to provide education opportunities for young workers.

Paul Yeung Siu-Hung, 62, co-founded the New Youth Study Society (新青學社) in 1977 with his college mates after graduation. It became well-known as the “workers’ evening school”.

At that time, only 60 per cent of students could enter secondary schools, while the rest worked as apprentices or child workers. Many of them were exploited because of their low education level.

Yeung and his friends hoped to empower these young workers through education. They taught a tailor-made, three-year course which included conventional subjects such as Chinese, English and mathematics, as well as industrial safety, the labour law and healthy eating to cater to workers’ needs.

Each founder invested HK$100 a month to rent a two-roomed flat in Tsuen Wan, which they transformed into classrooms. They even made furniture and donated books to set up a library corner. They promoted the school by posting street bills and attracted more than 20 workers in the beginning.

The government rolled out its policy of nine-years of universal education in the 1980s and this led to a sharp decline in new admissions. Finally, the New Youth Study Society closed seven years after it opened, in 1984. Yeung was content to accept the change. “We fulfilled our historic mission,” he says with a smile.

Today, workers’ evening schools no longer exist, and not many evening schools providing conventional secondary education are left. There are currently 10 government designated centres, and also some private evening schools. In the 2015/16 school year, the designated centres served around 1,300 students of all kinds and with different aims.

Ivy Yip Yuk-lan, 55, is studying Form five with her 18-year-old son at Holy Cross Lutheran Evening College in Tsuen Wan. Her son quit day school because he was bullied in Form Four. Yip, who completed a five-year evening school course 20 years ago, persuaded him to complete his secondary education in evening school. She hoped this will make it easier for him to find a job later.

At first, he refused because he had little incentive to study, but to encourage her son, Yip suggested studying together for three years so he would “not be alone”.

Her positive attitude worked and now mother and son study subjects such as biology and economics together. Yip is happy to be learning new things about subjects she has never studied before. She recalls the fun she had learning about enzymes in biology and gross domestic product (GDP) in economics. “If I do not learn new things, I will lose touch with society,” she says she always reminds herself.

Besides middle-aged learners, those repeating their school-leaving public examinations form a major part of the student body. Poon Ki-lam studied at MKMCF Ma Chan Duen Hey Memorial Evening College last year. He repeated Form Six while working part-time, in order to improve his grades and enroll in a nursing degree programme.

The 23-year-old, who is now studying nursing at the Open University of Hong Kong, says there are constraints and advantages in studying at evening schools. On the downside, students are limited to a three-hour class each weekday so teachers have to be exam-oriented. They prioritise examination content and skills but students might not be able to absorb the knowledge.

Poon studied biology. Sometimes, teachers could not finish the syllabus, let alone arrange laboratory work. Often he would have to read about processes in books rather than see them work in action through laboratory demonstrations and experiments.

He understood the time constraints so he did not just rely on his teachers. “You cannot demand that evening schools provide good services for you. You have to work hard on your own,” he says.

Despite the limitations, Poon thinks he was better off studying at evening school than by himself at home. “It is very important to have teachers to guide you, and friends with the same goal to accompany you along the way to public examination,” he says.

Teachers at the Holy Cross Lutheran Evening College acknowledge the difficulties of teaching in evening schools. Those teaching different subjects adopt different strategies to maximise the learning outcomes.

Wan Cheuk-yin teaches liberal studies. He emphasises in-class discussions and improving students’ exam-taking skills. He leaves the concepts for students to revise by themselves.

“Students’ work experience and background contribute to down-to-earth discussions, which are not possible in day schools,” says Wan, citing the example of a student who works in a hospital. He says the student could share stories about the actual difficulties medical practitioners are facing in a class on public health.

On the other hand, Wan’s colleague Yim Chun-leung, who has taught maths for 36 years, spends most of the time explaining mathematical concepts. Yim relies on students to do the exercises on their own because of the tight class schedule.

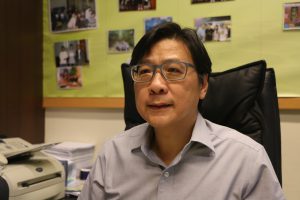

Apart from the inherent constraints, evening schools also face external challenges. Ken Cheung Luk-kin, the principal of the Lutheran Church Evening Colleges, has witnessed the changing fortunes of evening schools over the years.

During its heyday in the 1990s, the Lutheran Church’s evening schools held 16 to 20 secondary Form 5 classes at the same time. The schools could earn HK$1 million profit from tuition fees annually without receiving government support.

Since 2003, the Education Bureau has stopped giving any financial support to evening schools and they now operate on a self-financing basis. The Lutheran Church’s evening schools only have two classes for each form and charge low tuition fees of HK$60 for three hours, so they can only break even.

“The profit-making era of evening schools has ended,” the 57-year-old principal says. The school has re-positioned itself as a social service provider which offers students a chance to repeat or to complete their high school education.

Cheung is struggling to find ways to sustain the schools. He explored different options, such as starting children’s playgroups and offering courses on workplace English or International English Language Testing System (IELTS) preparation. However, he abandoned these plans because it is hard to compete with established providers such as the British Council or the big tutorial schools.

Instead, he is thinking of providing insurance and real estate management courses next year to attract more students. “We will not just sit still and wait for ‘death’, but every idea is challenging,” he sighs.

Similarly, the Queen’s College Old Boys’ Association (QCOBA) Evening School is also experiencing dropping admission rates. In the early 2000s, the school had 300 to 400 students but it has around 20 this year. The school is kept alive by donations from the alumni of Queen’s College and from the public.

Jessica Li, the principal of QCOBA, thinks there are several reasons for the decline of evening schools. Firstly, the number of students has dropped over the years due to the low birth rate. “Day schools are reducing classes or closing down, not to mention evening schools,” Li says.

Secondly, there are too many alternative paths for post-secondary education. After the handover, the government set a target that over 60 per cent of secondary school graduates should enter tertiary education. It greatly expanded the tertiary education sector, offering qualifications such as the Diploma Yi Jin (DYJ) and Associate Degree. Before this policy change, repeating and retaking public examinations was the only option available for students who wanted to further their studies.

Li is not totally pessimistic but she is cautious about the future of evening schools. She predicts that when the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination (HKDSE) has been in place for five years, the number of repeaters will increase and they are potential students of evening schools. The schools can also target new immigrants whose academic qualifications are not recognised in Hong Kong.

Still, she will monitor the enrollment situation closely. In the worst case scenario, if the number falls below five, she will probably close the school. At the moment, she thinks it is still acceptable. “Although there are not many students, as long as the demand exists, we will continue to operate,” Li says with determination.

Mervyn Cheung Man-ping, the chairman of Hong Kong Education Policy Concern Organisation, graduated from Queen Elizabeth Evening School in 1972. He studied there for six years and taught there for five. Cheung feels an intimate bond with evening schools so he still follows their development closely.

Cheung thinks a lack of promotion of evening schools is one reason for the low enrollment rates. For instance, he says, the Education Bureau has actively promoted post-secondary education programmes such as the DYJ and Associate Degree by organising exhibitions.

However, he adds that other post-secondary education programmes cannot replace the function of evening schools because they cannot help students to consolidate a secondary education foundation.

“For those students whose public examination results show they haven’t reached a certain required standard, why shouldn’t we [help them] receive basic education again?” says Cheung.

He says the other programmes cannot do much to help students build a solid foundation in basic skills such as English proficiency.

“But now people opt for other programmes as a shortcut and neglect the fact that they are below society’s required [academic] standard,” he says.

When pondering the survival of evening schools, Cheung suggests the focus should not be on thinking of ways to encourage students to study in them, but to rethink and reaffirm the true value of evening schools and the role they can play today.

Edited by Wing Chan