By Samuel Chan, Elizabeth Cheung, Lam Cho-wai

Partisan and Proud

There was nothing showy about the star. But the atmosphere was as much rock concert as it was political rally,“Ing-wen! Ing-wen! I love you!” shouted members of the crowd –supporters of Tsai Ing-wen, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) candidate in January’s presidential election.

The DPP and its allies form what is known as the Pan-Green camp in Taiwan politics. And among those wearing their political colours literally at the rally were some green-clad reporters and news photographers.

These journalists are very proud of their political stance but insist it would not affect how they report the news as that would be determined by their media organisation’s editorial stance.

It is not just individual reporters, Taiwan’s media organizations are not shy to run unabashedly partisan headlines. On the day after the election in which Tsai lost out to her Kuomintang (KMT) rival, Ma Ying-jeou, the dailies ran headlines such as “MA YING-JEOU HAS WON! THE 1992 CONSENSUS HAS WON!” and “THE FUTURE OF TAIWAN CANNOT BE SOLD”.

Such headlines suggest the news stories in the papers are unlikely to be free of bias. While completely impartial and objective reporting is an ideal that often remains just that, having a highly partisan media is almost accepted as a fact of life in Taiwan.

The island’s media organisations are usually aligned with either the Pan-Blues which consist of the Kuomintang (KMT) and its allies and the Pan-Greens.

The KMT-led Pan-Blue coalition favours closer economic links with the Chinese mainland while the DPP-led Pan-Green coalition favours eventual Taiwan independence. A newspaper betrays its allegiance easily through its headlines, layouts and photo arrangements.

A Fact of Life

Some Taiwanese are so used to partisan politics in the media that they do not feel the need for change. Ms Guo, a KMT supporter, says a political stance is merely a selling point for newspapers or television channels.

What really matters to her is the accuracy of news, which she believes is not affected by the political stance of a media organisation. “That’s why I would still opt for Pan-Blue newspapers for neutral news,” she says. Guo only reads the traditionally Pan-Blue China Times and United Daily News.

.Members of the younger generation may read more than one newspaper and browse news feeds provided by search engines to gather the information to form their own thoughts.

Taiwan’s journalists are themselves only too aware that news organizationsare rarely politically neutral. “When covering election news, media are advocates, not neutral bodies,” says the deputy editor of the Pan-Green Liberty Times, Tzou Jing-wen.

Tzou says there are reasons why a newspaper reports stories the way it does. The length of a story and where it is positioned implies which candidate the newspaper prefers.

Having said that, Tzou does not believe this is a problem. She says American newspapers such as the Washington Post and New York Times are known for their clear political standpoints. “It is acceptable to have your own standpoint as long as it is limited to the editorial only,” Tzou says.

She does, however, agree that news stories should not carry any personal viewpoints, while avoiding commenting on the reporting style of her own newspaper.

Ho Jung-shin is a China Times editor but he used to work at a Pan-Green newspaper. He says many newspapers show their stance in both news stories and editorials. However, he points out that even among the partisan press,, some offer a more diverse range of voices than others. “Some newspapers have one voice only. They support either the KMT or DPP unconditionally, with little room to accommodate other opinions,” he says.

Birth of the Pan-Green Press

The current split in the political stance of the Taiwan media began to develop after the end of the martial-law period, during which dissent was not tolerated in the media. The lifting of martial law in 1987 saw the growth of newspapers and TV news channels inclined to the Pan-Green coalition.

The long-suppressed local Taiwanese finally gained press freedom as Taiwan moved towards democracy in the late 1980s and founded their own newspapers like Liberty Times and TV channels such as Sanlih E-Television. However, the hostility between the two sides was harder to eradicate and the current state of the media reflects that

Trivial Pursuits.

Apart from the prevalence of partisan politics in the media, the ‘trivialisation’ of TV news reporting is also pervasive. For instance, it is not at all surprising to find a report on the presidential election immediately followed by a ‘news’item about the release of a pop singer’s new album.

The Taiwan media are famous for their obsession with amusing and heart-warming anecdotes.

“Why didn’t you kiss your wife?” was the first question asked by a local television reporter, after Ma Ying-jeou had just finished addressing cheering crowds at his campaign headquarters in Taipei after the election result was announced.

Instead of just focusing on how his victory might affect cross-straits relations, Taiwan reporters asked Ma questions like “how will you reward your wife for her long-time support?”

Such ‘cultural differences’ caused several Hong Kong reporters covering the presidential election in Taipei to roll their eyes. They said they would have been given a talking-to if they had asked the Chief Executive candidates the same questions.

“What is the point of this question?” said one Hong Kong reporter, “I guess it is again the debate of ‘public interest’ and ‘interest of the public’ in journalism.”

Many Taiwanese, however, are used to watching “serious” news and showbiz gossip in the same news programme.

“You may be baffled by this kind of programming but the Taiwan audience is used to the style,” says a business student surnamed Zhu.. “I guess mature citizens have the ability to tell the significant from the trivial.”

Zhu says most Taiwanese care about politics as well as the entertainment industry, so the news programmes are just giving the audience what they want. “I don’t see these two are in conflict. I wouldn’t want the same type of news all day long.” But Zhu admits that this kind of programming might lower the quality of serious news.

Lo Ven-hwei, journalism professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, explains the ‘trivialisation’ stems from the proliferation of 24-hour television news channels on the island. “There are seven television channels running news 24 hours a day. Since there are not many newsworthy stories to report, a newscast often becomes packed with soft and human interest stories,” Lo says.

National Chengchi University journalism professor Lin Yuan-huei says such an environment is not conducive to the rational public discussion of important issues. People tend to blame those who take a different political stance. “Someone may say ‘I don’t like this policy because he is from the Pan-Greens’, it is obviously not a good way to discuss and debate,” says Lin.

Independent Media?

The media should provide a platform for discussion and help foster a consensus on public issues. “For some bigger issues such as whether Taiwan should be independent, we can never reach a consensus because people from both sides seldom listen to each other! But Taiwan media have failed to create a good platform. One day, the Taiwan people will pay,” Lin says.

Even the supposedly politically-neutral public broadcasting service in Taiwan (PTS) is not free of government influence according to Lin. In addition to the fact that most PTS employees have the same political stance as the ruling party, Lin accuses the Ma Ying-jeou administration of exerting “significant but implicit” pressure on PTS.

Critics like Professor Lin are disappointed with the Taiwan media. “Local media have to change!” he says. Citizen and independent journalism could be a channel for change.

In 2010, citizen journalists revealed the government had acquired farmlands from the locals in rural villages by force. Their video clip soon went viral on the Internet. “But the local media did not investigate into such news at the beginning. You could imagine why. Yes, it is because of the KMT government, Taiwan media did not take up their responsibility,” Lin says.

Citizen journalism, a possible hope for the future of Taiwan media, is still in its infancy. Resources are limited, mostly it relies on journalism students who are not yet constrained by the pressures of revenue and readership. Despite all this, Lin remains optimistic and looks forward to positive changes in the industry.

Taiwan’s experience so far would seem to show that press freedom does not necessarily lead to quality journalism. But just as they have the freedom to choose their leader, the people of Taiwan also have the option of saying “no” to media that falls short of expected standards.

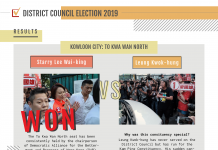

The Morning After

We bought two dailies on the day after the election and compared their reporting styles. The first three pages of the pro-KMT United Daily News were full of stories and photos of the re-elected President Ma Ying-jeou. No articles about Ma’s main opponent, DPP candidate Tsai Ing-wen was found until page four. In contrast, we noticed that Tsai received significantly more coverage in the pro-DPP Liberty Times. Her photo appeared together with Ma’s on the cover story, followed by three pages of photos of emotional DPP supporters. It also emphasised the narrow margin of Ma’s victory and describes it as the result of “KMT and Chinese Communist Party’s collaboration” in one headline.