Middle-aged Hongkongers hold different and changing views of Umbrella Movement

By Thomas Chan, Henry Lee

Pointing to a blue tent on the kerb, 23-year-old Leona Ho proudly proclaims, “This is my home!” The graphic designer comes to the occupied area in Admiralty almost every evening after work and does not go home until the middle of the night. That means she gets as little as three hours of sleep every day, but she is determined to stay, “as long as there are people here.”

Ho was infuriated by the police’s use of pepper spray on student protesters after dozens broke into Civic Square at the end of a week-long class boycott on September 26. As a result, she joined tens of thousands of protesters in occupying key financial and retail districts in Hong Kong.

While many protesters, mostly youngsters and students, are urged by their worried parents to return home, Ho receives texts from her father with messages such as, “I’m proud of you.”

“My dad told me if I were arrested, he has enough cash and could bail me out,” says Ho, “I have realised since high school that my parents are very different from others.” Never once has her father imposed his views on her; instead, he often encourages her to think critically and to draw her own conclusions.

This open-minded father is Herman Ho, who also supports the democratic movement. Even though the older Ho has not received any tertiary education, his immense interest in history and politics makes him an avid reader. He works as a night-shift security guard at a local school and uses the long hours to browse news websites and even pores over his daughter’s history reference books. Each day, he scours several newspapers at different ends of the political spectrum. The pro-democratic Apple Daily, the largely pro-establishment Oriental Daily and the pro-Beijing Wen Wei Po are all part of his daily read.

Ho thinks part of the reason people oppose the democratic movement is because they do not have enough knowledge about how the political system works. “Many people that are against the movement do not understand what civil nomination is, or the split voting system or functional constituencies,” says Ho. “They don’t understand and they don’t want to understand because they are scared of things that they cannot comprehend.”

But Ho believes that as a supporter of democracy and as a citizen, he has a responsibility to understand the unfairness of the political system. “When you absorb a lot of information, you’ll see how distorted the political system is,” says Ho. “But many Hong Kong people seem to think it’s too perplexing and would rather not care.”

Juggling work, family and many other things, few Hongkongers of Ho’s generation can afford to spend as much time as he does to keep themselves updated with current affairs. Some can barely grasp the meaning of simple political terms, let alone the intricacies of the policy-making process. For them, politics is out of sight, out of mind.

“I rarely read about politics because I find it irritating,” says 41-year-old Chan Hung-lai. “We aren’t really affected by political issues…We’re fine, no matter who’s the leader.” Chan, who holds an MBA degree, is currently a homemaker with a baby and a primary school age child. While she initially sympathised with the students and protesters, she is now feeling fed up because the occupation is disrupting her life and seemingly leading nowhere.

Chan, who lives near Mong Kok, used to take her son to primary school by taxi. But during the Mong Kok Occupation, the five minute ride had to be replaced by a half-hour walk. The fight for democracy is fine, she says but it has gone on for long enough. “It is affecting our lives. Roads are blocked, we have to walk to school and traffic is obstructed,” she says. “It feels like they’re throwing eggs against rocks…what can you achieve in the end?”

With two sons to take care of, Chan has her hands full. Though the family subscribes to Sing Tao Daily, a middle-class but politically conservative paper, Chan barely has the time to read the papers or watch the television news. “To be honest, the news [about the Occupy Movement] is all very similar … I’ve already got sick of it,” she says, “You cannot actually tell who’s right or who’s wrong.”

However she says she has noticed how biased the newspapers can be against the civil disobedience movement. She recalls reading an article blaming the closure of a restaurant on the occupation, but she knows the restaurant had been struggling even before the protesters took to the streets. “It is simply trying to smear the movement. [The incidents] are completely unrelated,” she says. It was not the first time she came across news items portraying the movement in an unfairly negative light, but Chan says she will exercise her own judgment in deciding whether or not to believe them.

While casual readers like Chan have noticed individual incidents where news reports appear to be smearing the Occupy Movement, others have studied the media landscape in recent years and seen a worrying trend of traditional media adopting increasingly conservative editorial positions. This is particularly pronounced on sensitive political issues like the Occupy Movement.

“Obviously they’re trying to frame issues or movements … in a way that serves their interest,” says Professor Francis Lee Lap-fung from the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). “For example, they will always emphasise the presence of so called foreign powers or foreign interests in the movement. These are different ways to characterise or frame the movement to make it look very questionable or make it look very bad.”

The pressure, he explains, stems from media owners’ financial and political ties with the Mainland. “Most Hong Kong media dare not enrage the Chinese government…Most of them [media owners] are business people and almost all of them have very many important business interests in China. And many of these media owners are themselves actually part of the political system,” says Lee.

Some see the trend as a result of Beijing’s moves to tighten control on information flow and sway public opinion in Hong Kong. How well the strategy is working is open to debate. “What has transpired in the past month shows the limitation of the power of traditional media,“ says Lee.

“If you really look at all the newspapers, all the negative headlines, public opinion should have turned against the movement very, very early on, but as a matter of fact, it didn’t.”

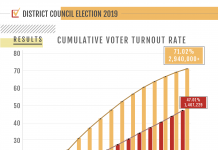

Polls conducted by Lee and his colleagues at the Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey of CUHK in October showed those supporting the movement increased by 6.5 per cent compared with September and those against the movement decreased by more than 10 per cent in the same period. In the initial weeks of the movement, public opinion seemed to turn in favour of the movement with 37.8 per cent of respondents supporting it, slightly more than those against.

However, as the impasse between the occupiers and the government went into a second month, the tide of public opinion began to turn. Poll results released in November put the percentage of respondents against the movement at 43.5 per cent, compared with 33.9 per cent who still supported it. Around two thirds of respondents wanted to see the movement end but more than half thought the government should offer concessions to end it. The impact on businesses caused by the occupation fuelled growing discontent against the movement.

In response, the movement’s supporters tried to engage the community by organising outreach activities, visiting affected neighbourhoods and knocking on doors in an attempt to win back support.

While the movement may not have brought about any concrete results yet, it has already successfully triggered the political awakening of many Hongkongers, who had originally been politically apathetic. Sanna Tsang, 43, was on her way to dinner with her friends when she learnt on social media that police were using tear gas to disperse protesters at Admiralty. “We immediately changed route and headed to Admiralty [to support the students]. We were bewildered. How could that happen?” she recalls.

Tsang, who finds reading traditional newspapers very tedious, describes her life as “only work and play”. “I only care about what to eat or drink, where to travel. I’m politically indifferent,” she says. “I was like a normal citizen. Go to work, get off from work and I don’t think much about the future.

But on 28th September, even after she returned home, she kept scrolling through her phone, looking at internet news to keep herself in the loop and try to process the whole incident. “I don’t understand why they have to treat students like this. It made my heart ache,” tears fall down Tsang’s cheeks as she recalls the scene. She began to ponder on what prompted the students to take to the streets and had led to the mounting frustration with Hong Kong’s governance.

For Tsang, who is used to sharing photos of her daily life and keeping in contact with her friends on social media, navigating social media sites to find information is a piece of cake. Now she feels as though she is addicted as she constantly checks her phone to keep herself updated. “I keep finding and following [pages] related to Occupy Central. I feel as though I’ve gone crazy, I would wake up in the middle of the night just to check what’s been happening,” she says.

As dissatisfaction with the conservative stance of mainstream media grows, readers are turning towards news disseminated in online social media platforms. Pages that gather news and information from amateur journalists have sprung up on Facebook, providing alternative sources of information and attracting tens of thousands of followers.

With a full-time job as a saleswoman, Tsang can only drop by the occupied areas occasionally, so she is delighted when she finds these pages that provide instant news on the latest happenings in the occupied areas.

However, encountering so many different voices and opinions on the Internet, Tsang sometimes feels baffled as well. “There’re a lot of different people portraying things differently on the Internet. I start to wonder if what I believe in is true. Am I looking at something real? … I will keep asking myself these questions.”

Perhaps she has yet to find a definitive answer. But by asking these questions, she has already taken a step into the battleground of competing information.

Edited by Rachel Cheung