Does free information flow change political opinions of Mainlanders in Hong Kong?

by Yan Li & Brian Wong

Hui Kei, a 29-year-old freelance writer from Zhejiang was once a Chinese patriot and firm believer in the Communist Party. He was an active member of the Young Pioneers and the Communist Youth League who would naturally stand to attention whenever the national anthem was played. Hui believed China would become powerful as long as it improved its military and economy.

In school, Hui learned that the June Fourth Incident in 1989 was a “political turmoil”. But he and his classmates did not pay much attention to it as they knew it would not come up in examinations. Rather, students were asked to express their opinions on Taiwan sovereignty and Falun Gong in exams. They knew they were expected to give “standardised” answers in line with the party position in order to score.

All this seemed perfectly normal and Hui never criticised the education and information he received in the Mainland until he arrived in Hong Kong in 2003 to join his mother who had married and settled here. In Hong Kong, he watched a documentary about the 1989 pro-democracy movement in China and the subsequent government crackdown. He realised what a huge difference there was between the account he saw and the version he had learned, and how serious media censorship was in China. “[After watching the documentary], I instantly doubted my previous education,” says Hui.

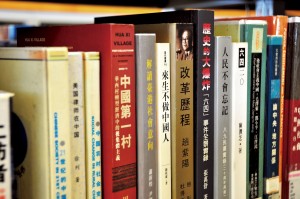

That was the beginning. Hui started to read books by liberal writers like Taiwan’s Li Ao and Hong Kong critic Leung Man-tao, which are hard to come by in the Mainland. He was inspired by the ideas of democracy and liberty and he was touched by the strong spirit shown by Hong Kong people in fighting for a better future for their city.

For Hui, Hong Kong has shown him “another way of Chinese existence”, such that he now finds China’s unification mantra increasingly annoying. “Looking back, I realise that Zhejiang people also have their own characteristics. We should not say we are Chinese. We should proudly say that we are Zhejiang people” says Hui. “‘Chinese’ is not enough to describe me.”

In Hui’s articles, he comments on the political situation in mainland China and Hong Kong. He also writes about the conflicts between the Mainland and the territory, and these articles are published on Mingpao Century and his personal Weibo account. However, his Weibo account is censored and only the people he has added and are following his account can view his articles. What is more, they can only view but not share his articles.

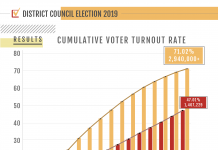

Media censorship is widespread and systematic. Apart from policing the content of traditional media outlets, mainland authorities also work to block sensitive messages on social media. Data from Weiboscope, an application developed by the Journalism and Media Studies Centre (JMSC) at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) to observe censorship on Weibo, reveals that 20 to 80 in every 10,000 Weibo posts are deleted every day. On September 28, the day the Occupy Central Movement was initiated, a record 150 posts were deleted out of every 10,000 posts.

David Bandurski, editor of JMSC’s China Media Project website explains that stability is the top priority for the Chinese government as Beijing believes “stability equals prosperity”. Therefore, the government censors any news it deems as “political threats” in order to avoid social unrest.

Apart from limiting what the media can cover, authorities also channel media coverage in favour of their own messages. Taking the Occupy Movement as an example, Bandurski says: “You can cover financial impacts, so if you’re covering the markets, you’re free to report and say, ‘Hong Kong stock market fell three points today’, otherwise the frames are all the same. Foreign conspiracy, western media prejudice…You can almost hear the opium war in the background.” As for information on the social media, people may not entirely trust what they see as they fear it may be only rumours.

Bandurski thinks that censorship, the channelling of information and unverified information on social media has caused a “crisis of credibility” in the mainland media. He says that while people know they cannot trust everything they see on Weibo, they also question the truthfulness and motives behind what the government tells them. “They don’t know what they can believe,” he says.

Jerry (who does not wish to disclose his full name) came from Zhanjiang to study government and law at HKU. The 21-year-old experienced a “crisis of credibility” in Chinese official media when he followed the reporting on the Wenzhou train collision in 2011 and noticed that while there was live coverage of the accident on Weibo, the state-run media did not report it.

When he was still in Zhanjiang, Jerry usually read Zhanjiang Daily and Southern Metropolis Daily, which are relatively more open and reliable than the state-run media. However, pressure from preparing the National Higher Education Entrance Examination meant he had little time to reflect on political matters.

When Jerry first came to Hong Kong, he was amazed by the city’s media diversity. “Unlike China, Hong Kong’s media landscape is very diverse. It has some formal [newspapers] like MingPao and some tabloid-style [newspapers] like Apple Daily; some are pro-Beijing and some are pro-democracy. It also includes many international media,” says Jerry. In Hong Kong, he subscribed to Yazhou Zhoukan and Time. He also reads the South China Morning Post online and read articles on the online news and views site, House News, before it suddenly closed over the summer.

Jerry says Hong Kong’s vibrant media environment has equipped him with greater knowledge with which to analyse political issues critically in recent years. “For example, in the Occupy Central movement, many of my classmates [in the Mainland] look at the matter from the “one country” perspective, but I will look at it from the “two systems” perspective,” he says.

His friends in the Mainland view the issue from the perspective of China’s governance and do not understand why Hongkongers are so keen on demanding democracy, but Jerry tries to explain the issues from Hongkongers’ points of view. He explains about the need for democracy in Hong Kong and the perceived distrust between the Leung Chun-ying government and citizens.

“I’ll try to be a communicator, sharing Hong Kong’s news and bringing the other side of information to my friends in the Mainland. I hope to influence them, just as Hong Kong’s media has influenced me before,” says Jerry.

A relatively free and open media environment may provide the resources for people to rethink and change their political stance, but changes are not guaranteed. Steve Guo Zhongshi, professor in the Department of Journalism at the Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU), says people do not just passively receive information from the media, they also actively choose the media that aligns with their stance.

Guo, who teaches China reporting and mass communication, says that whether the Hong Kong media can influence Mainlanders’ political views will depend on whether they pay attention to politics in the first place. However, media censorship can and does contribute to political apathy among young people in China. “Many people, especially the younger ones, care little about politics because it is useless. It does not change anything. It is this political apathy that leads to teenagers not usually talking about politics,” says Guo.

As for those who are more curious and interested in social issues, they may interpret and analyse what they receive from the media, but this does not necessarily lead to an obvious change of political stance.

Tony (who does not wish to disclose his full name) is a case in point. The 22-year-old from Guizhou is studying risk management at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Before he came to Hong Kong four years ago, he paid little attention to politics because of his heavy school workload.

In Hong Kong, he began to read books that are banned in the Mainland and to develop his own judgement on political and social matters. Tony prefers books and academic journals to reading and watching daily news reports because he thinks they are more objective. “News is biased, the stance of the newspaper determines their opinion, they [journalists] can write whatever they want,” he says.

But rather than becoming more critical of the Chinese government, he has become more understanding of its strong and centralised leadership, including the way it handled the student-led protest in 1989. “Now I think it was necessary [the decision made by the government in the June Fourth Incident]…For Deng Xiaoping, the country’s stability was very important. Political stability is the foundation for economic development, though it was very sad for the students,” he explains.

Tony says he has changed from having no view to looking at things from a pragmatic point of view after coming to Hong Kong. “Democracy was only a word to me before. Now I think democracy should be achieved step by step,” he says. For him, Hong Kong people are too idealistic in their pursuit of democracy. But he is afraid of sharing his views with local students in case they attack him for it. “I find it very difficult for local people and Mainlanders to communicate, no matter what I say, they say I’m brainwashed,” says Tony.

Tony is not the only one who is worried that he will be labelled as “brainwashed”. Galen Wong (not his real name), a 22-year-old mainland professional working in Hong Kong’s finance sector says what people call “brainwashing” is a political methodology that exists everywhere in the world, not just China. Wong says people have a choice over whether to believe the “brainwashing” ideas or to learn more. Wong says Mainlanders generally refuse to discuss sensitive political issues not because they are being “brainwashed” but because they do not want to get into trouble.

Like Tony, Wong thinks there is an abundance of information in Hong Kong and like Tony, he tends to take the pragmatic approach when analyzing political problems. He says the livelihoods of Chinese people have improved significantly in the last 30 years. As they can now enjoy a good life, they do not really need a change. “The histories [of Hong Kong and mainland China] are different, the circumstances are different. We have different mindsets,” says Wong. “I admire Hong Kong people’s courage [in fighting for democracy], but is it really practical?”

With access to a wider range of information in Hong Kong, Mainlanders here may turn out to be more liberal or conservative than they were before. But regardless of the outcome, Hong Kong’s media and information freedoms have provided them with the materials to further develop their own opinions and think critically beyond the great firewall.

Edited by Vanessa Cheung