Relatives who devote their lives to those with mental health problems are themselves vulnerable and neglected

By Elaine Tsang & Jeffrey Wong

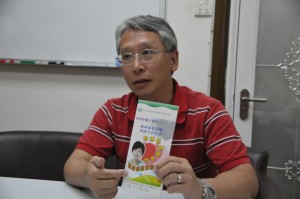

Mico Chow Man-cheung remembers the times when he would stare at the ringing phone on his office table, his heart pounding and his hands clammy with sweat. At times like these, Chow would be filled with dread. He feared it would be a call from the police or a hospital. His wife, who suffered from depression, had previously threatened to end her life. He was afraid the call would bring bad news.

Eventually, Chow left his job of 25 years so he could devote his time to looking after his wife. What he did not realise was the pressure at home would threaten to drag him into depression too.

“Actually there was not much I could do to help because I didn’t have the knowledge to and I couldn’t see any ways through which I could help my wife,” says Chow. “At that moment, I was worried about whether I could handle my own moods and emotions.”

Adding to his concerns about how he would handle his own emotions were his fears that saying the wrong thing could further antagonise his wife. He took extreme care over his choice of words and avoided negative criticisms that might harm their relationship.

Chow’s wife is stable now and he has gone on to become the chairman of the Hong Kong Familylink Mental Health Advocacy Association. But he fully understands what it is like to be one of the many carers who are walking an emotional tightrope while taking care of family members living with mental illness. According to a survey by the Baptist Oi Kwan Social Service (BOKSS) in 2010, 70 per cent of such carers – most of whom are middle-aged women – exhibit various levels of depression symptoms.

Tim Pang Hung-cheong is a community organiser at the Society for Community Organisation, (SOCO) who advocates for the rights of the mentally-ill and their families. Apart from the emotional strains, Pang says carers also have to shoulder great financial pressures. Like Chow, some carers quit their jobs to become full-time carers. Without a stable source of income, the demands of medication and therapy become a constant headache.

Treatment is available through the public system but the median waiting time for public hospitals is around seven weeks and the longest waiting period can be up to 100 weeks. Once a patient gets an appointment, consultations may last just a few minutes. Therefore many carers prefer to send their family member to private hospitals or clinics which they believe can provide better services. However, these services can cost thousands of dollars a week.

Another reason families may prefer to seek private treatment is to avoid having medical records in the public system which could affect the patient or their family members’ future career.

“A patient’s family member applied for a job as a civil servant in the Hong Kong Customs and Excise Department, but he was rejected because of the family record of mental illness,” Pang says.

Stigma and discrimination surrounding mental illness are still widespread in society and can be an obstacle to family members’ acceptance and understanding of people with mental illness. Yet it is essential for carers to have an understanding and knowledge of their family member’s illness.

Take schizophrenia for example. It is a severe mental disorder that affects around 1 per cent of the population worldwide, with the most common age of onset being between 15 and 35. People with schizophrenia exhibit symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, disorganised speech and a loss of motivation and interest. Pang says that if the family carer does not understand the illness, it is easy for arguments to develop and blow up.

“The illness makes people have lower motivation to finish the tasks they are told to do, like cleaning themselves, taking their medicine,” says Pang. When this is met with the carers’ demand for compliance and obedience, disputes can erupt.

Lily Chan, whose daughter has schizophrenia was once a controlling and demanding carer. Chan’s daughter was in Form Four when the symptoms of the illness began to emerge – first, she refused to go to school and was expelled. Then, at home, she started to talk to herself occasionally. Chan took her to see a doctor and she was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1993.

But for the first seven years after the diagnosis, Chan did not fully accept the reality of her daughter’s condition. Neither did she know how to communicate with her well. Whenever Chan’s daughter refused to comply with her instructions, she would scold her severely and they would start quarrelling. Chan distanced herself from friends and family as she felt ashamed whenever people asked about her daughter’s condition.

“People have misunderstandings about mental illness, that it is the result of evil deeds committed by the family. I didn’t dare talk to anyone about it,” she says.

It was not until the family experienced a traumatic accident that Chan and her husband were jolted out of denial and finally learned to take the initiative in dealing with the condition.

Their daughter had been occasionally refusing or reducing her medication and this triggered a re-emergence of the illness in 2000. One day, after tidying up her daughter’s room, Chan told her sternly not to mess it up again. Her daughter was very angry, picked up a knife and stabbed her mother in the head.

Luckily, Chan survived. “Looking back, this [stabbing] is a blessing in disguise. Since then, I have learnt to seek help from the community,” she says.

After the incident, Chan and her husband began to seek assistance by consulting social workers and clinical psychologists. They learned to appreciate and praise their daughter, and to avoid criticisms. By taking a different perspective, she was able to understand the incident, to build trust and to find hope.

“She was too angry and simply wanted to protect herself, though she didn’t know how to control her emotions,” she now says of her daughter’s actions.

Eunice Lee Tsz-ying, a social worker from BOKSS understands Chan’s initial reaction to her daughter’s illness. When a person becomes mentally ill, their personality and temperament change, they seem to have “changed into another person, living in another world”, as Chan puts it. This puts immense pressure on the carers as they struggle to make sense of reality.

“The families say it is like they have lost a family member,” Lee says. “On the one hand they have to take care of the patient; on the other, they have to bear the transition period of their ‘loss’.”

Lee thinks that, like Chan initially, many carers resist seeking help due to the conservative atmosphere in the community, where speaking out may trigger a sense of shame and self-blame in the Chinese context.

Chien Wai-tong, a professor at the School of Nursing of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, has been studying the role of the family in the recovery of the mentally ill for nine years. He says family intervention is important for both the initial discovery of the illness and for the recovery process.

Chien says the family carer is the first and most crucial person to discover the illness and gauge the needs of the person with mental illness. This is important because early diagnosis and treatment with anti-psychotic drugs and psychotherapy increases the chance of successfully controlling the symptoms.

The family plays a supportive role in the treatment and recovery and, in order to do so, Chien says family members need to learn how to control the “amount” of emotion they display in their interactions with the mentally ill person. “The lower the ‘expressed emotion’, the lower the rate of relapse of the illness,” he says.

Yet, despite the central and often indispensable role that carers play in helping patients recover from mental illness, there are no official counselling services or training programmes specifically aimed at carers. Currently, they have to rely on a few non-governmental organisations like BOKSS, SOCO and Hong Kong Familylink Mental Health Advocacy Association, which provide training workshops and self-help groups for carers. Due to limited resources, these are usually small-scale operations that can only serve a limited number of people.

Hong Kong lags behind countries where the treatment for mental illness is family-based; instead the government adopts a policy that relies on patients themselves to seek help. The emphasis is on medication of the patient and other factors. Family carers are considered supplementary in the recovery process.

“Owing to the high costs, prevention is rarely carried out. If outreach services are provided, it would help to get people on treatment sooner and lower the relapse rate,” says Chien.

In 2010, the Social Welfare Department launched 24 Integrated Community Centres for Mental Wellness (ICCMW) to try and provide social support for people with mental illness and aid the re-integration of mentally-ill outpatients into the community. Patients’ family members are included as one of the target groups of the service.

However, Carmen Wong Lai-moy, a former clinical supervisor in one of the ICCMW on Hong Kong Island, says due to insufficient manpower, ICCMW’s staff are overwhelmed by the number of patients they have to serve, let alone their family carers.

Pang from SOCO agrees with Wong that the allocation of resources is worrying.

“In one ICCMW, there are around three administration staff, eight social workers, one nurse and one psychiatric therapist. With only 24 ICCMW serving 18 districts in Hong Kong, there is an imbalanced distribution of support,” says Pang.

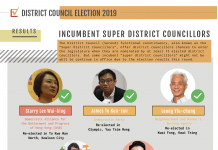

Legislator Peter Cheung Kwok-che, who represents the social welfare functional constituency, believes the government needs to revise the existing mental health medication system. He says there needs to be a more objective framework of assessment for treating patients, stating the treatment approach and giving a projection of the resources required. A timetable should then be drawn up for the allocation of resources.

Cheung believes the community needs to be involved too and that those on the frontline should be setting up concern groups. “Talking about community care, we should come up with a policy by public discussion, and no longer confined to the experts’ level,” he says. Cheung says such discussion could inspire community education which would help to eliminate stigma.

The case of Lily Chan’s daughter shows that with treatment and family and community support, even people with severe mental illnesses can lead full and independent lives. Her schizophrenia is under control, she has a job and is living in a halfway hostel which she chose herself. She visits her parents every weekend and the family has encouraged her to apply for public housing. It has not been easy but Lily Chan and her family are relieved their daughter is able to start a new life.

“A table has four legs and a car has four wheels. Likewise, medication, community support, family care and the patient himself [makes a full recovery package],” says Chan.

Chan says she apologised to her daughter after the stabbing incident. Together, the family learned to express their emotions properly to foster effective communication.

“My daughter asked me, ‘Mum can I come back? Are you still angry with me?’ I said you are part of me and I will always love you,” Chan recalls. “Love eventually heals all.”

Edited by Stephanie Cheng