Insufficient and inadequate provision of sports and recreational facilities mar cohesion in the community

By Eunice Ip, Ryan Li

In the morning at Tai Po’s Wan Tau Tong Estate, elderly residents queue to pick up free newspapers and to squeeze into fast-food shops in the shopping mall for breakfast. Wan Tau Tong is a small district packed with public rental housing estates and home ownership scheme flats. There is a sizable elderly population but apart from the shopping mall, few recreational facilities where senior citizens can spend their time.

Recreational and sports facilities are places people go to socialise, to get healthy and to relieve stress. They can enhance cohesion in a community and play an important part in determining how livable a community is. But to fulfill these important roles, they must match the needs of the communities in which they are found.

Do Hong Kong’s sports and recreational facilities fit the bill?

Tai Po is one of the districts which face the most serious aging problem in Hong Kong. According to the Planning Department’s Projections of Population Distribution for 2015 to 2024, the number of residents aged 60 or above in Tai Po is expected to rise from 67,100 in 2016 to 104,300 in 2024. This will create an increased demand for health services and it makes sense for the government to encourage the elderly to exercise more to stay fit and avoid illnesses. The problem is, for those elderly living in Wan Tau Tong, there is nowhere to go within striking distance.

Wan Tau Tong’s district councillor, Ken Yu Chi-wing, is disappointed with the lack of facilities for the elderly in his district.

“We often persuade the elderly not to stay at home, and they do listen to us. But even if they are willing to go out, there is not much they can do when they go downstairs,” he laments.

Although the government is aware of Hong Kong’s ageing problem, it seems few districts have actively developed sports facilities for the elderly. The legislator for the social welfare functional constituency, Peter Cheung Kwok-che, says the government has failed to adopt an “elderly mainstreaming” approach which would take account of the needs of the elderly in policy-making.

Cheung agrees with building more recreational facilities and organising sports classes for the elderly. However, he points out it is difficult for them to walk long distances from their homes to exercise. Therefore facilities should be located in each district to encourage the elderly to exercise frequently.

This is something that Wan Tau Tong district councillor Ken Yu is only too aware of. However, he and his fellow district councillors do not have the final say in deciding on which infrastructure projects are built.

Instead, that responsibility falls to the District Facilities Management Committee (DFMC). The DFMC’s were set up for each district in 2008 and membership comprises district councillors and government officials from various departments. The committees will negotiate with government departments over the various proposals and those that are passed will be submitted to the Legislative Council for funding approval.

For example, every district councillor in Tai Po can propose two projects, of high and low priority, to the District Facilities Management Committee (DFMC) every year. Ho

wever, according to Yu there are two major problems with this system.

Firstly, the facilities eventually built may differ from district councillors’ original proposals. Yu explains the DFMCs spend large sums of money on consulta

ncies to study the feasibility of the proposals received, and to make amendments if necessary. He says the consultancies may come up with useless facilities, such as rain shelters that cannot block rain. These problems are then left for district councillors to deal with.

Secondly, the committees do not usually approve large-scale projects due to their high costs. Even if they are passed, it takes a long time for construction to begin. For example, the sports’ centre on Plover Cove Road in Tai Po, was proposed in 2009 and was approved by the committee in 2011, but is still awaiting funding approval from the Legislative Council.

Apart from procedural issues, the way projects are executed presents other problems. Outside Tai Po Plaza, there is a cycling track which is divided into several short sections. The segmentation of the track and its proximity to the crowded shopping mall makes it inconvenient for cyclists.

For Yu it is a reflection of officials’ desire to tick the boxes rather than take into account users’ needs. “I think it only reflects that the government is very stupid,” he says.

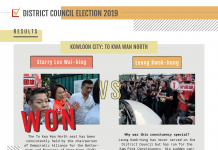

Tai Po is not the only district to experience a mismatch of, or inefficiencies in, resource allocation. Tin Shui Wai, which comes under the Yuen Long District Council, has a large young population. Instead of the elderly, the district is filled with energetic teenagers. According to the Census and Statistics Department, 14 per cent of the population was aged 15 to 24 in 2014, meaning Yuen Long has the highest proportion of young people among all districts.

With such a high concentration of adolescents and young people, the area would benefit from more sports facilities. However, residents bemoan a lack of venues to exercise and take part in sports. Chan Kai-lun, a college student living in the area says: “Tin Shui Wai is a residential area with high population density, if there are more sports and recreational facilities, our lives will be better.”

According to the Hong Kong Planning Standards and Guidelines issued by the Planning Department, there should be one standard swimming pool per 287,000 people, but despite having a population of 292,000, Tin Shui Wai does not have one.

Kwok Hing-ping, district councillor for Yat Chak in Yuen Long, blames the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD).

“The less you do, the fewer mistakes you make,” Kwok says of the attitude of LCSD staff members when handling requests from the district council.

Kwok says he thinks the department is reluctant to construct more facilities because it wants to avoid being given more responsibilities and financial burdens. “They have higher management burden if they build one more facility. Management means that it requires more resources,” he adds.

Kwok also believes the LCSD lacks knowledge on how to use land effectively. He suggests that it should follow the practice of some private housing developments and build sports facilities such as badminton courts in the corridors between buildings.

Another district that suffers from inadequate facilities is Sai Kung. Despite the picturesque views and semi-rural environment, it is hard to find a cycling track in Sai Kung. The LCSD says this is because some roads in the area are too steep and are not suitable for building cycling tracks as children may not be able to cycle safely on them.

District councillor for Sai Kung Islands, Philip Li Ka-leung, thinks this is just an excuse.

“Why can’t they build some cycling tracks that are not for children?” he says. “You can put a sign up there to explain the possible harm, and people can choose for themselves whether or not to cycle in the area.”

Apart from a lack of facilities, residents also complain about the planning and design of the recreational facilities they do have in Sai Kung. For instance, there is a small model boat pool of about 20 sq. m. in the Hong Kong Velodrome Park in Tseung Kwan O. Model boat owners say that once a boat is switched on and accelerates, it has already reached the other side of the pool. Li points out that there is a huge artificial lake right next to the model boat pool. He does not understand why the larger pool is not used for the model boats instead.

Li says the government’s focus on new residential developments means it attaches little importance to the need for adequate and appropriate sports and recreational facilities in the various districts.

“If the government is not planning to build residential buildings in the area, why would it have the incentive to construct a swimming pool for you?” he says. To him, the building of sports facilities has now become a bargaining chip when the government wants support for building new residential blocks.

The cases of Tai Po, Tin Shui Wai and Sai Kung illustrate some existing problems with the building of sports and recreational facilities. In these cases there are neither sufficient nor adequate facilities to meet local demands. However, there are also instances where people have complained of the excess supply of certain facilities.

For instance, the LCSD currently manages more than 40 gateball courts. Gateball is a game played with a mallet, similar to croquet, and is mainly enjoyed by the elderly. According to a written reply from the LCSD, the utilisation rate of these courts is on average around 40 per cent, way lower than for other facilities such as badminton courts and swimming pools.

Some attribute the low usage rates to two reasons. First, these gateball courts only accept bookings in person, lowering the incentive of residents to use the facilities. Second, the LCSD is not flexible in managing these courts in that they are not made available for other uses.

However, according to the LCSD, these courts are supposed to be open for other uses. This is echoed by Catherina Lau Lee Lai-fong, the chairperson of the Hong Kong, China Gateball Association, who says that “courts are now opened by the LCSD to the public after complaints in 2014.”

Varsity called various gateball courts as a member of the public to ask whether or not the courts are available for other uses and received a wide range of responses. One LCSD staff member from Sha Tin District said gateball courts could only be used for specific purposes, therefore other uses, such as playing badminton are prohibited. Meanwhile, a staff member from the Tuen Mun District said it takes up to two to three months to get approval to use the courts for other purposes.

Although the LCSD has set up guidelines for the usage of gateball courts in all districts, it does not necessarily benefit citizens and the low utilisation rates of gateball courts continues to be a problem.

It does not always have to be this way. Sai Kung Islands district councillor Philip Li cites the case of a squash court in Sai Kung which was under-utilised. It was later turned into a table tennis court to meet the needs of local residents. Li says this shows it is possible for the LCSD to listen and respond to public opinions.

In recent years, the government set up various community programmes such as the Community Sports Club Programmes and the District Sports Teams Training Scheme. They aim to promote “Sport for All” and to encourage people from all backgrounds to maintain active and healthy lifestyles within the community.

However, to Kwok Hing-ping, district councillor for Yat Chak in Yuen Long, you need more than just slogans and signature campaigns to create healthy communities and competitive athletes. “The Chief Executive said he wanted to improve the quality of athletes in Hong Kong, but you just don’t have the right facilities to help them,” he says. “LCSD is saying one thing, but doing another.”

Edited by Mavis Wong